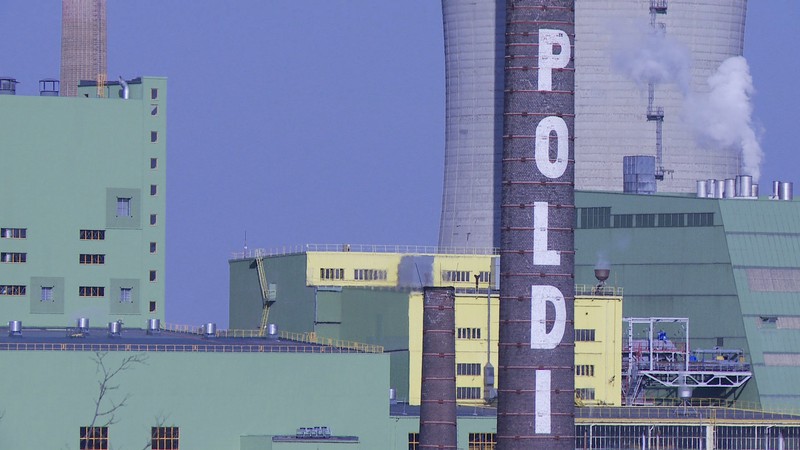

A Show in Poldi Kladno Steelworks

One of the two films that garnered a Special Mention in the Jihlava IDFF’s competition section for the Best Czech Documentary Film was Tears of Steel: Vladimír Stehlík Meets Lubomír Krystlík by the newcomer, Tomáš Potočný. The film follows the tragicomic story of Vladimír Stehlík, the former CEO of Poldi Kladno Steelworks, who, although long retired, still cannot come to terms with the fact that his once famous factory is already a history. In an interview with dok.revue, Tomáš Potočný offers a look behind the scenes of the film’s shooting with a protagonist who was very hard to work with and a one-day meeting of old friends and colleagues that actually saved the film.

Your film Tears of Steel: Vladimír Stehlík Meets Lubomír Krystlík recounts the fates of the former CEO of Poldi Kladno Steelworks, Vladimír Stehlík. What do you as a documentarian think about this rather controversial figure?

The film as a whole made me realise how problematic it is to make complex judgements and to draw simple conclusions. In the 1990s, Stehlík was someone else than who he is today. In the early 1990s, he was a very charismatic figure, a capable businessman and factory manager. I do believe that he was a good manager at the time when he was about to take over the management of Poldi Kladno. However, his later failures have made their mark. But I’m not in the position to judge whether it was due to his own mistakes or due to political circumstances; the only thing I can rely on is media reports from the period, presented with various intentions and reflecting the interests of various people. However, I no longer have the possibility to analytically reconstruct the company’s accounting, and I am not able to disclose deficiencies in his management or decision-making – which, after all, was never my aim.

Was it difficult to work with someone who publicly presents himself as an unbreakable man and who uncompromisingly asserts his own opinions?

My collaboration with Stehlík was alternately difficult and good. At one point he was very friendly to me. He even talked to me on familiar terms, which I didn’t object to, but I kept my distance. There’s a great age difference between us, we’re about forty years apart. He saw me as a student who was interested in his story. But then there came a moment when he stopped trusting me, thinking I was an agent of the enemy who stole his business from him. Moreover, he is so preoccupied with the case that it is almost impossible to discuss anything else with him. For me as a director, this wasn’t easy at all.

You must have spent quite a lot of time trying to figure out, how to efficiently handle the film and the collaboration with Stehlík.

I tried different strategies to see what would happen and what possibilities would open up. And I found out that it would be extremely difficult to show a situation different than just Stehlík speaking on the camera, because the camera worked as a magnet that provoked Stehlík to lead monothematic monologues. I originally wanted to lead a dialogue, but any questions would only spark further monologues. But we gradually came to find the key. We organised a meeting of Stehlík and some other people who witnessed the turbulent nineties but, in addition to this kick-off, we didn’t stage anything, we only observed the situation. And we came up with a couple of suitable questions.

Tears of Steel: Vladimír Stehlík Meets Lubomír Krystlík

Is this why you invited Krystlík, Stehlík’s personal consultant?

Yes, and it was a big thing, because they hadn’t seen each other for several years. They both respect each other, but they are both very dominant. They have worked together throughout their whole career, they met in the 1980s. Krystlík is an older gentleman and opera singer well-versed in the etiquette who advised Stehlík on how to act, dress and what and how to say. He has retained his mentor-like attitude to this day, and it is clear that he still wishes the former boss of Poldi Kladno to carefully consider what political events to support, to choose words and not to use foul language. And their relationship is still tense. Who dominates the game? The CEO or his advisor who, in many respects, tells him what to do? You can clearly see that in the film.

How much time did you spend shooting with both of the protagonists?

The meeting of these two gentlemen took place within a single day, but we spent almost three years making the film. It was very strenuous to actually ask questions and to provoke an interesting interaction between these two men. It took me some time before I was actually able to choose my questions effectively. And then I just asked, for example, about their heroic moment at the international conference in Düsseldorf and the reaction was immediate.

Did you follow a script or was the interview improvised?

My initial idea was to have an informal conversation with Stehlík about the past and the situation in the business and what it’s like to fall down from the top management of a big company and live on a meagre pension. I hoped he would perhaps unintentionally reveal something from the background of big business, for example how he had to handle negotiations with the prime minister or a foreign partner. I hoped that we would draw a portrait of the 1990s in the Czech Republic on the backdrop of this reflective dialogue. However, I didn’t manage to stimulate this kind of a reflection. Stehlík’s mind works in a different mode than I actually imagined and neither patience nor higher frequency of meetings helped. He kept on repeating his statements regarding the case and he did so in a very stylised manner. My entire effort to open a space for reflection was in vain and my script started to collapse.

What was then your key to shooting a film that won one of the two Special Mentions at this year’s Jihlava IDFF?

The cameraman, Honza Šípek, was a great help – he was telling me that the footage was great, although to me it didn’t seem so. My acknowledgments also go to Míra Janek, whose studio I attended at school. For a certain period of time, I was frustrated and thought I wouldn’t be able to finish the film, because the only thing it shows over and again is the position of a wronged man. Then I managed to organise a meeting with Krystlík, which indicated that the key to the film is to be less serious about it, to add more humour. And all of the relations and the whole situation in the 1990s surfaced on the secondary level.

So you started to approach the film as a show, exactly in line with the opening suggestion of the film’s protagonist.

This clearly articulated decision was made at the editing stage, but during the shooting, we only tried to focus on the less serious moments and to provoke them. However, Stehlík never viewed the film as a show. On the contrary, considering the overall length of the footage, there are not that many moments that could be seen as humorous. And the footage naturally contains a thousand more utterances than the film, we have something like eight shooting days that never made it into the film.

Tears of Steel: Vladimír Stehlík Meets Lubomír Krystlík

You made a film about the CEO of Poldi Kladno Steelworks, the decline and management of which made headlines in the 1990. But you offer hardly any solution or explanation of the events, why?

Because I don’t find it important to deal with what investigative journalists have on their agenda. I am not interested in what actually happened at that time, I wanted to show the atmosphere of the 1990s. And I also tried to shoot a film about the life story of a man, Mr Stehlík. I wanted to capture the transformation of a successful businessman into a pensioner who, as the newspapers say, has to live on less than a hundred crowns per day. I saw a great potential right from the start, especially in combination with plentiful archival sources.

So you made a film about a famous case without actually focusing on the case.

It was never my intention to focus on the case. Later during the shooting, I actually deliberately avoided the question, “What actually happened?” . I didn’t even have to ask the question aloud, because Stehlík was giving the same answer all over again. And it wasn’t my goal to make an analytical and investigative film, I didn’t contact Stehlík’s former colleagues and rivals to hear them out and to confront his position with their version. Of course, I needed to understand the case myself, but I didn’t mind that some of the events had blurred contours. I read many articles from the period and consulted TV archives – and I knew that what I was confronted with was only one perspective of the entire story. Stehlík’s case was attractive for media, which, in many cases, judged him unfairly, for instance when reporting on the “one-crown breakfast affair”. When, still as a CEO, he started to offer his employees subsidised breakfasts, a media surge followed, pointing to Stehlík’s alleged irresponsible expenses in a situation when his company wasn’t doing well. But nobody tried to look for a deeper motivation behind this strategy. Stehlík inherited a socialist plant including the workers who were used to having a breakfast after their arrival to work in the morning. The plant was already in operation, but it was basically idle for the first hour or so. And a big plant like this one generates high costs, and one hour per day brought about significant losses. That’s why Stehlík offered his employees breakfasts for one crown before their working hours. It wasn’t such an economic blunder.

You spent over two years shooting with Stehlík. Having put the Poldi Kladno case into a new context, what do you think of Stehlík’s role? Is he guilty or not? Is he to blame for Poldi’s bankruptcy?

Stehlík wasn’t accused of bringing Poldi to bankruptcy, you can’t blame anyone for the fact that their business goes bankrupt. They accused him of misusing information during business transactions and of breach of trust, simply pointing to the fact that at the time when it was clear that the business would go bust due to loss of funding from the Komerční Bank, Stehlík transferred some shares and funds between individual companies within the Bohemia Art consortium. I am neither an economist nor a lawyer and I can’t tell which of these transfers were in line with the law, and which were not. But I guess that before the decline of Poldi Kladno, there was no indication of asset stripping or any transactions that were going on in other companies.

For the first time in 18 years, Jihlava’s best Czech documentary competition section, Czech Joy, didn’t find its winner. You and Tomáš Kratochvíl received the jury’s Special Mention – what does it mean to you?

To me, this verdict was somewhat unhappy because what the jury’s statement actually said was that none of the films was worthy of the title of the best Czech documentary film. It’s not about me not winning the award, my film is modest and it is more or less a DIY work made together with Honza Šípek. However, I was sorry that the jury only noticed it’s qualities in this context. I would have been happier if there was an actual winner of this competition with Tears of Steel receiving a Special Mention, which would be much more of an honour. It’s unfair to all of the selected films but also to the programmers – we’re left in an embarrassing void indicating that the competition featured no interesting film. And I am not sure how many readers scanning media reports will realise that this is not an objective verdict, but an opinion of a five-member jury.