Chris Marker

The multifaceted Chris Marker (1921-2012) was a personality constantly shrouded in mystery. The main reason for publishing this monograph is to help tear down the unnecessary mystique that prevents Marker’s films from reaching a broader audience, because his entire audiovisual oeuvre is an important reference point for the study of art history in general and – naturally – film in particular.

“Film is not incompatible with intelligence. Here it is not a question of the intelligence of the filmmaker, rather of the previously only somewhat acknowledged idea that the intelligence could be found in the source material, the raw material from which the commentary and the editing proceed, obtaining from them an object, namely Film.”

- Chris Marker

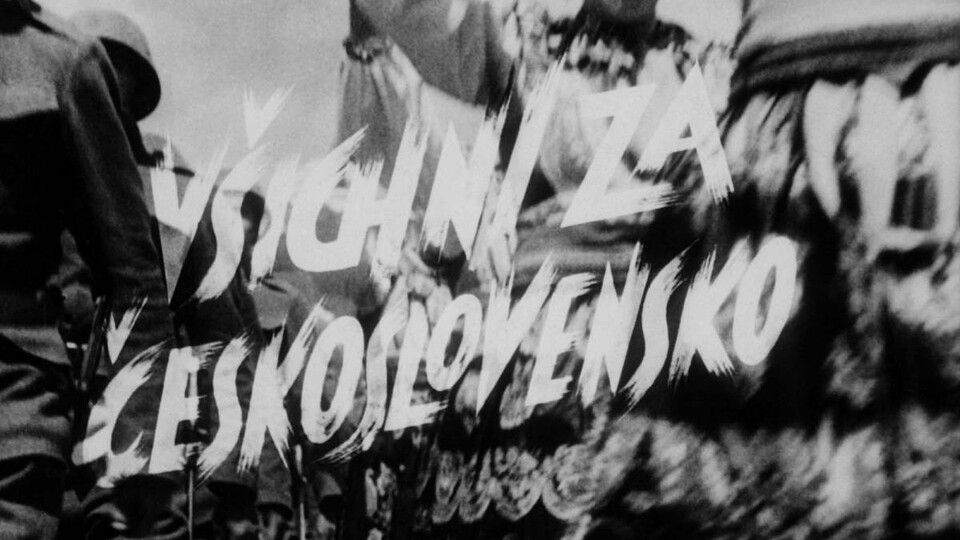

Marker first called attention to himself as a director in the 1950s and ’60s through original essay-style films such as Letters from Siberia. If we closely analyse Marker’s work, we see that it closely mirrors technological developments in cinema and the increasingly blurred line between film and new media, including the internet. He initiated numerous important cinematic projects, such as the collective political work Far from Vietnam, and collaborated on many important films by other directors.

Unlike most foreign publication, this book is not a collection of essays analysing the main subjects of Marker’s work. It is ordered chronologically, with original Czech texts on Marker’s various artistic phases, and pays detailed attention to Marker as an author and journalist.

This book presents the first Czech translations of his inspirational scripts to the imaginary films Soy Mexico and America Dreams. It also contains includes several studies by foreign authors, offering among other things an original look at films such as La Jetée, Le Joli Mai, and Sans Soleil that Czech audiences are the most familiar with.

This monograph is based on years of research and study of Marker’s work, and presents an overview of selected information, knowledge, and commentary, thus sparing anyone interested in Marker’s work the time and effort they would otherwise have to expend wading through an overwhelming amount of data and information instead of letting themselves be carried away by legends – as the director himself had wished. Last but not least, this publication should serve as an informed guide through the world of an exceptional artist. Chris Marker died on his 91st birthday in the year of this book’s publishing, leaving behind an extensive body of work that will never be completely catalogued, for he saw his films as living organisms with a limited lifespan; he preferred that some would be forgotten and even refused their public screenings.

Marker contributed to the book in the form of several valuable comments, and above all by helping to compile one of his most complete filmographies, including a list of his multimedia and internet projects. The book also contains explicatory texts and information on copyright.

“Chris Marker himself contributed to the book with his comments and advice. He helped to compile his most complete filmography to date, which includes his unique multimedia and internet projects. At the same time, he contributed several observations that helped to define the book’s conception and to clarify certain details regarding his work. This monograph also looks at one of Marker’s most important films, Le joli mai. A new version of this film, completed during Chris Marker’s lifetime, was shown at Jihlava.”

- David Čeněk, the book’s author and selector for the Jihlava IDFF

Chris Marker La Jetée, or a Filmogram of Consciousness

Philippe Dubois

“Chris Marker is a pure soul.”

- Jonas Mekas

Before I delve into “my subject” (my dear, good subject), I would like to here quote from a lesser known text by Henri Bergson, in which he again addresses the questions of time and movement, moment and duration, present and past, memory and its renewal, and finally questions of consciousness and the relationship that it evokes in our mental perception of life and death. Later, we will have an opportunity to see that his ideas essentially lead us towards the philosophical essence of film and photography. It is this essence that Marker’s film La Jetée is about.

“What exactly is the present? If it is the current moment – that is, a mathematical moment that is related to time as a mathematical point is to a line – then it is clear that such a moment is a mere abstraction, a mental point of view. It cannot have any real existence. You could never create time from such moments, just as you cannot create a line from mathematical points. [...] Our consciousness says that when we talk about our present, then we are thinking of a particular interval of duration. How long does it endure? That cannot be precisely determined; it is something quite fluctuating, that may be shortened or extended depending on what attention we pay to it. [...]

Let us go even further: in an enduring present, an infinitely expandable attention will be focused on as large a segment of duration as we choose, meaning that it will also include what we call our past. [...] If attention to life is sufficiently strong and sufficiently unbound by all practical meaning, it would contain, within one indivisible present, the entire elapsed past of a conscious person – not as in a snapshot, not as a whole consisting of simultaneous parts, but as something that would at the same time be in continuous motion. [...]

This is not just a hypothesis. In exceptional cases, it may happen that our attention all of a sudden ceases to be focused on life, and immediately the past is magically made present. It would appear that persons who are unexpectedly confronted by the threat of immediate death (for instance, a mountain climber who falls into an abyss, a drowning man or a hanging victim) are capable of experiencing a sudden change of attention – like a change in the focus of their consciousness, which had previously been looking towards the future but is suddenly absorbed by the necessity to act and loses interest in it. This is enough to remember thousands of ‘forgotten’ details, for the person’s entire life to play out in front of him in one animated panorama.”

(Dubois, Philippe. La Jetée de Chris Marker ou le cinématogramme de la conscience. In: Dubois, Philippe (ed.). Recherches sur Chris Marker. Théorème. Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2002, pp. 8-45.)

We are thus truly faced by an “enduring present”, an intensive time where the difference between past and present disappears in favour of an inherent flow, thanks to which one’s entire life is made present at the moment of death. This pure substance of time within the individual’s consciousness may be called the immediate memory of all of time. In short, it is something that would look like a cinematic dream captured on one single photograph. And such a dream exists, a film that tells a story while simultaneously being its formal dispositif: Chris Marker’s 1962 La Jetée, a short film lasting “only” 29 minutes. It has been frequently noted that, as far as length goes, Chris Marker (whose initials are the same as the French acronym for short film – court métrage) never actually shot a “normal” film – only short films or (very) long ones. This of course tells us nothing, except perhaps that time is not a “standard” for Marker; it is not measured, but is infinitely flexible and vertiginous. This short film, however, managed to tell the entire life of one man by condensing it into an unbelievable moment-image. It is a fascinating film, one that is – and will remain – absolutely unique and just as mythical. It is, if you like, Marker’s only film with a story (what is more, a science-fiction film). In my eyes, the film is so intense that although it feels like a theoretical act – something like a film-idea that formulates complex conceptual models

(of time, space, representation, the life of the mind) – it is also a pure work and not a mere illustration of a conceptual exercise. It is the progeny of a living, irresistible force without equal, before which all of theory pales by comparison. Precisely these two reasons are why this work interests and fascinates me, just as it has fascinated several generations of theorists and artists, this author included. “La Jetée is the only of my films about whose presentation I learn with delight,” Chris Marker liked to say.

David Čeněk’s book Chris Marker can be purchased online at the Jihlava IDFF store.