How to read television using The Television Handbook

Television is the “daily media bread” of the population; however, there is only a handful of works that reflect on this phenomenon, either from the theoretical or the practical perspective. There is practically no comprehensive study that would address the issue of television in its entirety. The uninterrupted flow of the fluid of television broadcasting, numerous channels, a wide range of various programmes and many technological innovations makes it problematic to maintain the requisite distance from the issue, thus also rendering it difficult to comprehend and perceive television as a sociocultural phenomenon. In consequence, except for sporadic attempts, there is still a lack of analyses of the television landscape on the Czech book market.

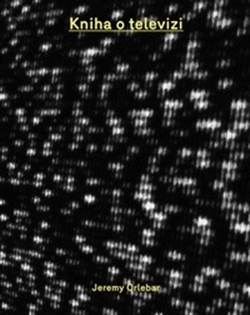

The Prague‘s AMU Press has therefore decided to compensate for this lack by publishing a Czech translation of The Television Handbook by the British author – producer, lecturer and TV director Jeremy Orlebar. This refreshing work the fourth updated edition of which has been translated by Helena Bendová, is definitely a valuable read, even despite the fact that it focuses primarily on the British television landscape.

The book is impressive especially in terms of its extent, topicality and also its concept. It is divided into six parts, in which Orlebar tries to outline the current television trends as well as theoretical concepts supported by case studies and factual information. Moreover, it also serves as a practical guide to television production as well as basic introduction to key names and terms associated with television industry. The merit of the book also consists in a decent bibliography at the end of each of the twenty-three chapters containing references to numerous foreign studies on television, and a glossary of selected terms at the end of the book.

TV boundaries of documentary film

In the part entitled “Factual Television”, Orlebar provides fans of documentary film, among other things, with an overview of specific elements characteristic for some of the documentary film types. His classification of the variants of the documentary film format also includes a number of original observations, for instance a comment on creative documentaries. Orlebar has noted a recent trend that this type of documentary films is no longer made primarily for television but they are intended for cinema release. Because the current tendencies of television broadcasting move toward the presentation of an increasing number of factual programmes, creative documentaries will eventually appear on television, but in the form of “feature films, thus avoiding any regulations regarding bias and balance” (p. 86). The fact is that in the UK, television legislation strictly requires that standard television news, documentary and news programmes must not be biased but provide multiple perspectives of the problem, thus aiming at apparent “objectivity” and “balance”. By means of this mechanism, creative documents, although distinctly accentuating the author’s perspective of the problem concerned, are included in the television schedule despite British regulations.

On the other hand, the prism of objectivity together with the criterion of realistic representation is now and then randomly violated in the very text of Orlebar’s book, thus leading to questionable conclusions that the author himself fails to decipher satisfactorily. In a chapter entitled “Documentary” he does not hesitate to compare individual types of documentaries with an “objective documentary”. Here, he presumably means “observational documentary”, the objectivity of which he himself questioned several pages earlier (and also in the following chapter “Making Factual Programmes”). Although in the chapter dedicated to documentary films, Orlebar outlines the possible script-writing and drama conceptions and rules applicable to various types of documentaries, the chapter “Reality TV” also includes the section “Boundaries between Authenticity and Performance”. At the same time, it is at least questionable, in view of the above-mentioned facts, whether such boundaries are not only an empty concept and whether these two notions are actually each other’s opposites. Moreover, it is not clear why the section has been included in this particular chapter and not in the chapters focusing on documentary film. And it must be admitted, that the contradictory arguments in the individual parts of the text and the varying balance of information are not an uncommon occurrence in The Television Handbook, which, together with the not so commonly used terminology makes a rather confusing and non-systematic impression.

How to describe television?

The above-mentioned textual problem draws attention to the concept and structure of the publication. The Television Handbook is actually not a linear text, but a cluster of autonomous shorter texts. It rather resembles an encyclopaedia, replacing the alphabetical order with topical arrangement. Orlebar pushes the boundaries of traditional studies by including texts showing various qualities, thus creating a varied, although not always well-arranged, almost hypertext composition. However, the structure of The Television Handbook most of all resembles its own subject – television broadcasting. It assembles texts of a varied nature, length, level of subjectivity, information depth, and representing different perspectives. The essay style is transformed into a medallion of the author, then into a handbook, or a fill-in form for performers. However, it is unbelievable that Orlebar has managed to create such a complex image despite the pitfalls of such a mosaic form.

As a result, The Television Handbook thus provides an integrated view of the contemporary, mainly British, television broadcasting. Using a playful mosaic of texts, Orlebar does not try to solve the problems of television analyses, rather offering a substrate in relation to which the mind of a critical reader raises numerous key questions. There is no doubt that a set of questions need to be raised primarily in cases where there is practically no defined area of interest or literacy background. Orlebar’s multi-faceted view should not be missed by anyone who is interested in the issue of television broadcasting and wishes to obtain in-depth knowledge of the television landscape. At the same time, it will certainly be a useful as a basic and well-arranged publication for those who intend to get acquainted with the topic because The Television Handbook, similarly to television broadcasting, offers something for everyone. Nevertheless, in both these cases it is evident that reading that is sufficiently critical is an integral part that pushes the boundaries of knowledge.