Mark Cousins. Creativity is like a contagion

Last year, for the first time in the history of the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, a documentary won the top prize – A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things by Mark Cousins. From his deep love of cinema and thoughts on film curation to aging, Parajanov’s tea, and the need for wildness, our conversation explored the many layers of his artistic vision.

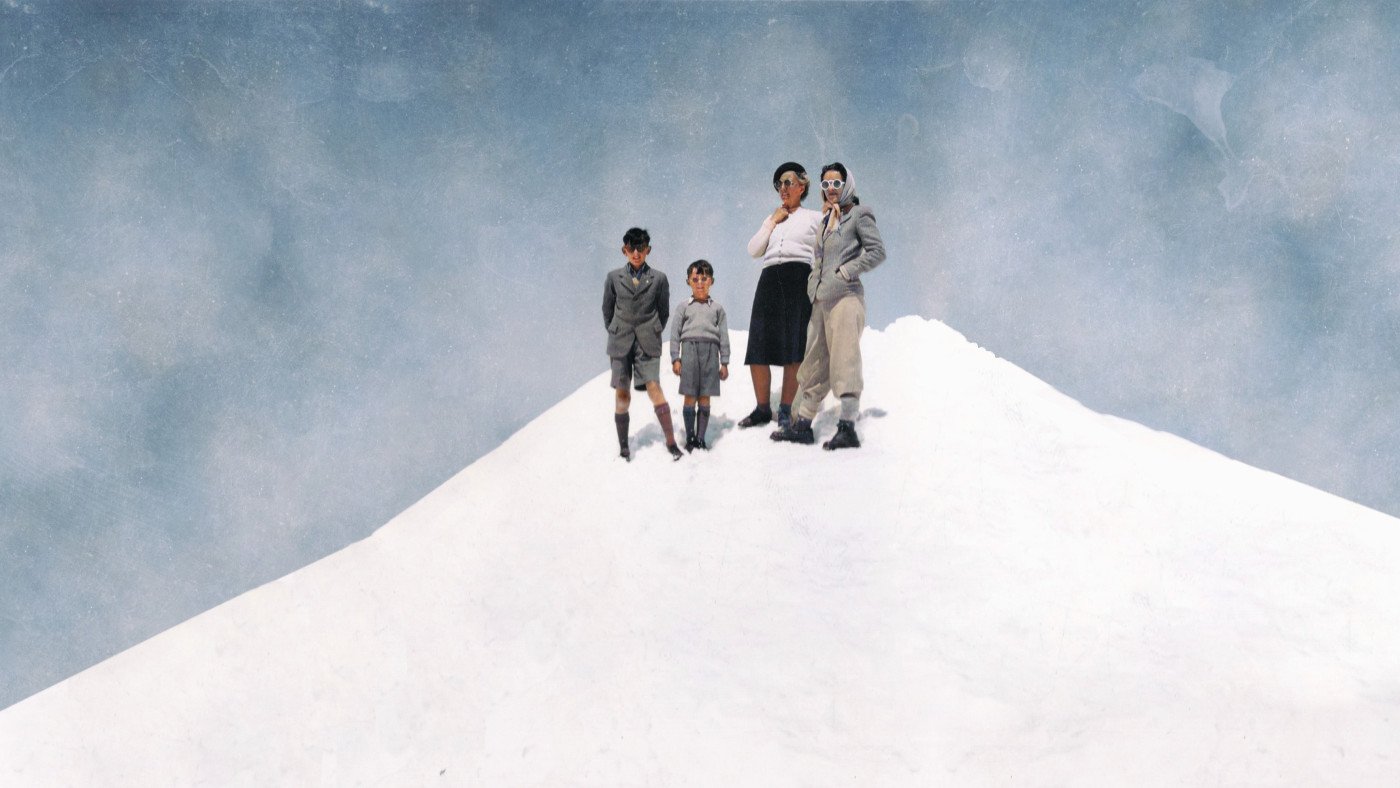

After Scottish painter Wilhelmina Barns-Graham climbed the Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland, her perception of the world changed forever. Until the end of her life, glacial colors and shapes permeated her work. This is precisely what captivated director Mark Cousins. In A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things, he brings to life both this defining experience and the artist’s unique way of thinking. He does so through her paintings and his signature commentary. When we spoke over Skype, I caught him in his study room in Edinburgh.

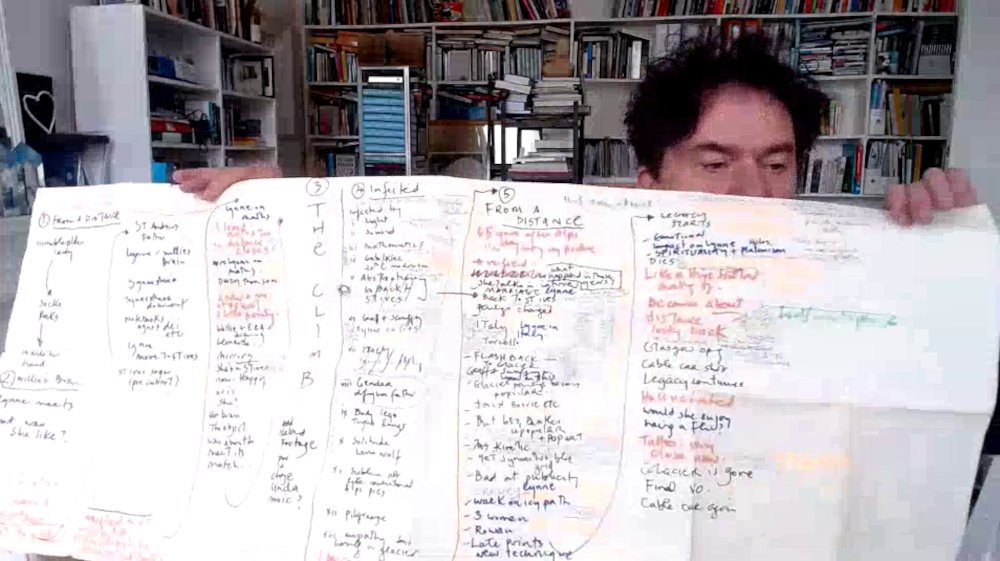

When I attended your masterclass in Sarajevo last year, you showed your writing process on a giant roll of paper. Was this film, A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things, created in the same way?

Yes! I can show you! (unfolds an A0 sheet of paper) For me, it all works the same way. The structure comes first. Then we edit. Finally, I write the voice-over. I have "camera, editing and script" in the credits of all my films – in that order. The text comes last. That's a fundamental principle for me.

When making Sudden Glimpse I had a sheet with the structure hanging on the wall here in the studio and we worked from it. You can see the chapters on it: From a Distance, The Climb, Infected. The orange parts are other materials, the blue parts are the bits where I show up.

This paper is much smaller than the one you brought to Sarajevo for The March on Rome. Why is that?

The March on Rome has loads and loads of archive footage in it. I gave each archive a little piece of paper. That's why it was much bigger, to move those bits of paper around. It's sort of the way that David Bowie worked when he was writing a song. But while The March on Rome was much more complex, A Sudden Glimpse seemed quite simple to me.

I knew that I would place the climb up the glacier in the middle, followed by a kind of infection by the experience. I ended up naming the chapter "Infected". She was infected by the climb, and then I have been infected by her. It's that idea of creativity being a kind of contagion or illness.

What first brought you to Wilhelmina Barns-Graham?

I first encountered her work in the 1980s in Edinburgh during an exhibition of her work. It was like I had met someone who thinks like me, mathematically. Like-minded people can spot each other across a crowded room. And I spot a fellow traveler in the world of grids and structures.

Did you know at that time that the glacier played such an important role in her life?

The very first images I saw were the ones with the glacier. And I quickly read and discovered that this central, pivotal moment in her life had happened. I'm very interested in epiphanies. The idea that a single moment can change everything for a human being. I'm not a religious person. But in India, there's this word darshan, which means “pull back the curtain to reveal the divine”. This was a kind of darshan for her.

She encountered something like an eternity in that moment, her own sense of smallness. We've all had that at some time when we're on our own in a landscape and you suddenly feel so small in a great way.

Why did you wait so long to make a film about her?

Back then, I was making films on quite political subjects – neo-Nazis, Holocaust deniers, the First Gulf War… I didn't think I would ever make films about art, even though I'd studied art history.

Then, quite recently, I tweeted an image of Wilhelmina and the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust, which looks after her estate, saw it and invited me to see her archive. So I went – and I was overwhelmed. I I hadn’t realized how productive and obsessively compulsive she was about painting.

The film's narrative doesn't focus on her life story; we don't learn a lot about her personally but rather how her mind works, which is related to her synesthesia. What did synesthesia mean for her?

You're right. It's not a biographical film. I’ve tried to avoid the more conventional ways of narrating. I was always interested in innovation and also used to say I would do no biographical films. And this is my fifth.

Willie’s life was not that dramatic. I've been interested in the imagination of the person, not the life story. I really reject this idea that to know somebody, you need to know the biographical details of their life.

There’s a lot of research on synesthesia, and the best explanation is that it comes from extra connections in the brain. Most people’s brains don’t link colors and numbers directly, but if you have additional pathways, you might see red and immediately think of the number five.

I believe this is closely related to the creative process. Creativity is all about making unexpected connections, and people with synesthesia have a natural advantage—they already experience these unique associations. In a way, they have a head start in the creative game. Beyoncé, for example, is synesthetic.

Does your brain function similarly?

Partly. My brain is different, I am not synesthetic. At school I was a very slow reader. But I was very good at imagery, structure, physics, chemistry and maths.

So I had a very sciencey brain, and I still have tendencies in that direction. Art is my first love but I'm particularly interested in those artists who are structural thinkers, like Paul Cézanne, Tintoretto and a lot of the italian painters of the 1300. And of course Wilhelmina Barns-Graham.

How do you personally interpret Ralph Waldo Emerson’s quote, ‘The poet turns the world to glass,’ which you reference in the movie?

Isn't that a beautiful phrase? You know, Edinburgh is the city of the Enlightenment – a movement rooted in facts and science, crucial for transforming European society by dispelling superstition and reducing the dominance of religion. But the risk of that project was equating value solely with factuality.

The Wilhelmina Barns-Graham film challenges this idea. What if facts aren’t as relevant as we think? What if they’re just a kind of smokescreen? And what if the imaginative life, our way of perceiving nature, is actually the solid, enduring truth?

After all, glass is a really hard substance. That’s what fascinates me: that maybe the imagination is real and the biographical outer world is a kind of fantasy in some ways.

Speaking of facts. Your films often engage in a dialogue with works of art and their creators. You don’t state how things are; instead, you ask whether they are that way. In one interview, you mentioned that you absolutely despise "objective" documentaries.

Yeah, I hate the objective male voice, the lecturer standing in front of the classroom telling you everything. That's why this film is openly subjective. That's why I put myself in the film, because I really find the omniscient, usually male voice narrator boring. Show some emotion, some passion!

Wilhelmina eventually answers some of your questions in the film, and we learn what she found on the glacier. Are her answers written by you, or are they based on her diaries?

The sequence where she is talking to her younger self? That was written by me. I'm very interested in aging. I'm 59 now, and I'm looking back to my younger self and thinking: Am I that person? What do I remember of that person?

When older Willie talks to younger Willie and says “You're happier than I am, but I'm a better painter than you”, that's me speaking to myself. As we get older, we lose more – we suffer, we grieve and can't be as purely happy as in youth. But I'm a much better filmmaker now than I was in my youth.

You operated the camera yourself. How do you decide whether you will shoot or someone else will? Stockholm, My Love and I Am Belfast were shot by Christopher Doyle, who is also Wong Kar Wai’s cinematographer. March On Rome was shot by Timoty Aliprandi.

Chris himself approached me at the time. He shot about a quarter, the rest was done by me. He mainly did the really hard tricky shots like crane shots, which I can’t do. With Chris, we're quite similar in energy levels. We live life fully. We drink quite a lot of alcohol. I remember at one dinner in Sweden, we ended up both naked in a bath in a restaurant wearing only masks.

When I started filmmaking in the eighties, I was scared of the camera. They were big, even to do a simple scene, you needed a truck. And it was a super male environment. All these guys who were saying “Oh, you won't understand”. I would say I was feminized by them.

When the cameras got smaller, I thought that I'll try it myself. And I loved the process. I think I'm happiest when I'm filming. It is a really intimate process for me. I am carrying my cameras and lenses everywhere. But I never went to film school.

Has your life changed after making The Story of Film: An Odyssey? For me, it was the first time I heard about you when you introduced the series at Karlovy Vary.

Yes, completely. It gave me a lot of confidence. But since it was based on one of my books, making it actually felt a bit boring in some ways.

The creative kicks out of the key things it says, like Ozu is a center of cinema and not Hollywood, that we have undervalued female directors, that Africa is crucial to film history, that all already faded. To turn this into a very long film was both difficult, because we didn’t have a lot of money for it and I had to travel a lot, and boring. I was just jet lagged the whole time.

After that, I was very surprised at the reaction. Looking back, I understand it more. It's passionately international, that's why it's used in film schools in South Africa, Beijing, Australia and in many places in Europe. It changed my life. I got a lot of offers to direct other stuff and honorary degrees and PhDs. We won quite a few awards for it including the Peabody Award. And I was thrilled that it internationalized my reputation.

I'd already been passionately interested in the outer world. I drove from Edinburgh to Mumbai with my partner and that showed me how eurocentric the world is. And The Story of Film said: “No, the center is not us”.

But before that, you worked for a long time on BBC’s Scene By Scene, where you went through filmmakers' works with them, or Moviedrome, where you brought lesser-known films to television screens. How did you get into that?

I had been a filmmaker for the BBC. And then I ran the Edinburgh Film Festival. I was probably 29 but I looked younger and when you run a film festival, you're quite visible. I'd sit on stage with Bertolucci or the Coen brothers and talk to them about their scenes. Not a general conversation about their career, but specific scenes. And some TV people saw that and thought, they’d give me a go.

The first one we did was an interview with Sean Connery, filmed in my flat. Sean Connery never gave interviews to anybody, but he was a friend of mine, and we would go for a pizza. And that started it. Then he phoned Spielberg and people passed me around. It was like: “There's this young guy, but he's really knowledgeable about movies.”

I came from a working class background in Belfast and I was suddenly swarming around Beverly Hills hanging out with movie stars like Janet Leigh and Rod Steiger and really encountering a Hollywood sort of intellectual, creative, political world that I had been fascinated by, but never thought that I would actually penetrate.

When I got to the Moviedrome, all the presenters were white men and a lot of the subjects were quite macho. I tried to change that up. I put Douglas Sirk movies on there and a lot of the films I chose were about women.

So was your path to what you do more gradual, or was there a significant event, a breaking point?

Here in the UK, the fastest way to get into the film industry is to move to London. I didn't want to do that. As a sort of slightly anxious person, it scared me. But also as a working class Irish person, London seemed like a kind of metropolitan enemy in some ways. So I decided to stay in the celtic world, moving from Ireland to Scotland.

In Edinburgh, a city that I love, there wasn't much of a film industry. So my buildup was very slow, even though I started directing early. I'm glad because the first things I made were shit. I slowly got better. I found my voice as a filmmaker, tried different styles. Then I did this job at Edinburgh Film Festival, and suddenly my contacts book went from zero to a hundred.

That was a big jump. And then I stabilized. And then The Story of Film came out. And that was a big jump again.

And meanwhile, behind the scenes, I'm watching more and more films, starting to teach myself about how I can film my own movies. So I'm glad, I haven't peaked yet. I know that I'm still getting better, and the award from Karlovy Vary obviously helps, but I'm still feeling that I'm starting to speak the language of cinema better.

If you haven't peaked yet, what are your ambitions?

I don't measure these things in terms of outer success. Winning a prize it's obviously fantastic. It really encourages me. But there's also the inner eye, there's the thing that Wilhelmina Barns-Graham knew that she can't stop. Rainer Maria Rilke talks about a kind of addiction and compulsion in Letters to a Young Poet.

You have also written several books, one of which is about documentary films. How do you combine writing and filming? Is one more natural for you?

I've got a new book coming out in two weeks. It's called Dear Orson Welles and other essays. And that's my 6th book, but I don't think of myself as a writer and particularly good at words. Imagery is the language that I speak.

I think that through all the work and films one of the central themes is the pleasure of looking and the mental health aspects of looking. It is the fact that every time I'm feeling sad I just go out and look at people on the streets and imagine their other lives. Then I feel better.

I'm bad at lots of things, but I'm very good at looking at an image and sort of diving into it as if it's a swimming pool. With Willie Barnes-Graham's work, I just thought, I'm in them, not outside them looking, but inside them, which is a lovely feeling. We all want to escape ourselves. I find myself really quite boring, especially my thought processes. And so if I can get out of myself, then that's great.

In addition to immersing yourself in film images, you also draw attention to them. Because we have access to so much content, we are lost in it, but at the same time, we won’t just let ourselves be told what to watch. So what is the way forward for being a film curator?

I do think that people feel overwhelmed by choice. Curation is more important than ever in the era of overload. I almost never watch films at home, but I can go on streaming platforms and scroll through movies for 30 minutes and pick nothing. People want somebody to say: “Try this. Taste this. You might like it.”

When I was young, I was hungry for cinema, and I could get almost none of it. I read about Citizen Kane and then it took ten years before I could see it. Now you can probably see it in 10 seconds. That's great and joyous, but desire comes out of a gap, something that's unattainable. Cinema is very attainable now, so the danger is it becomes less exciting. If you want to see Paper Heads by Dušan Hanák, you can probably see it today. But there's something about waiting for cinema, the fact that cinema won't immediately reveal its pleasures. That's a very satisfying thing.

But how to do it differently today, when everything is so easily attainable? How to preserve the desire?

I wonder if there is a difference. Curation is storytelling. Curation is saying: “You know, there's something in the world that will excite you, and here's why”. You need to use the techniques of theatre and curation. When Tilda Swinton and I worked together, she and I have done a wide range of things over the years, and they were always wildly theatrical.

When we did our first thing, which was here in Scotland, we dropped all the lights and put a spotlight and moved it around and played a song. It could be The Smiths, or it could be Nine Inch Nails. I remember we were doing a Parajanov film. We gave everybody a cup of tea beforehand. We didn't tell them until the end, that the tea had come from Parajanov himself.

I think that most people want excitement. It's lovely to sit at home and watch Netflix and have pizza. But we all want excitement. And curation is the creation of excitement.

You also did a project with Tilda Swinton called 8 and ½, in which you introduced children to the exciting world of cinema. Does it still work?

No, it was only intended to go for two years. Tilda and I are both very busy people, obviously, but also, we don't want to run an institution. We’ve wanted to create a kind of firework display and then it's over. People thought of it as education. It wasn't at all. It was just about excitement. It was about creating a kind of magical, fun moment, a kind of bar mitzvah, almost, for a child. An introduction into the world of cinema.

You know what the mosh pit is at the front of a rock concert? I always think that we should try to recreate the mosh pit. You need a kind of wildness. George Bataille talks about “the Accursed Share”. When we've all done that rational stuff, when we paid our bills and when we’ve looked after our family, there's an extra bit in life which is wild. I meet an awful lot of people who think that the intellect is the way to go. To make a film you actually have to stop thinking. You have to really get in contact with your wild side.

In the film Maybe Life, you explore whether being naked makes one perceive things more sharply. What do you do to keep perceiving things clearly in today's image-saturated world, besides nudity? How to work on “the Accursed Share”?

Nakedness is a metaphor for other things, like exposure, honesty, gentleness and being open to risk. I'll jump on my bike and just go out and cycle. I have no no idea where I'm going. Taking a risk often doesn't pay off. But when it does pay off, it's fantastic.

And I must say my only problem with Maybe Life is that my co-author Maria appears fully frontal naked on screen and I don't. My editor made that choice and as a passionate feminist I think we should have changed that.

In your sixteen-hour series Women Make Film, you mention two Czech directors, Drahomíra Vihanová and Věra Chytilová. Do you have other favorite Czech filmmakers? What is your favorite Czech film?

I could have mentioned more, but at least I've got two in there. I really love Drahomíra Vihanová and her short film called Fugue on Black Keys. She made it in film school and it is a masterpiece. In terms of Věra Chytilová, I like all her films, but I also have the greatest affection for the early ones, especially for Something Different.

Also fantastic is Miroslav Janek's documentary The Unseen about blind children who take photographs. There are loads of documentaries about blindness, I could probably name thirty of them, but this one is sensationally good. And then Jiří Trnka's The Hand. This is one of the best animated films ever made.

How many films do you watch annually? Do you keep track?

Definitely not. I've watched two movies today, before our interview. And I will probably see something this afternoon. But I would never be able to do the Letterboxd thing. Once I watch a movie, I'm going to go and make paella or something.

But how do you remember everything? Do you make best-of lists, or do you not work that way?

Yes, I make lists in my head. I often get asked to curate specific things. Like funky films, or movies only about the year 1964 or films about bodies. I do that. I like doing stuff like that.

So what are your favourite documentaries?

Just off the top of my head, I would say The House is Black by Forugh Farrokhzad, the great Iranian film. On the Road by Noriaki Tsuchimoto. From India, it's Mani Kaul's Siddeshwari. From Germany it would be Marlene by Maximilian Schell, a portrait film about Marlene Dietrich, which is so brilliant, because he had to make an entire film about Dietrich without cameras, she said no cameras. The Lebanese director Alek Keshishian is great. From Latvia Juris Podnieks and his Hello, do you hear us? Viktor Kosakovsky's film Sreda is a masterpiece. And anything by Agnes Varda, particularly Daguerreotypes and The Cleaners and I, one of the greatest films ever made.

Personally, it's hard for me to pull any ranking like that out of my memory...

I didn't hesitate there, did I? No, because these are living things in my head. They are all there in my head, so it's easy for me to talk about them. And as you saw in my list, it wasn't a eurocentric list, was it? Cinema is the world. I should have mentioned Eduardo Coutinho from Brazil!

I heard your entire work as a curator started out of anger that people only talked about films like Godfather and Star wars. What makes you most angry today?

There is a lot to be angry about in the world. Gaza, inequality, the lack of social justice, homeless people, narcissism which we see in so many politicians these days.

I'm angry that more people don't know about Kira Maratova, an extraordinary Ukrainian filmmaker. I'm angry that there is still dominance in film culture.

There are a lot of films about male rage. The Searchers, Taxi driver, Raging Bull, Godfather, Citizen Kane. I love these films. And they are all about the same thing – angry men who cannot understand things like gentleness or empathy. Men that have no empathy at all, that makes me very angry.

You wrote a book with Kevin Macdonald about documentaries. You're not going to turn it into a movie?

That's what we're working on. We've got four hours done so far and we'll see if we present it next year or wait until the whole project is completed. I personally think we should start presenting it. Most influential film I've ever made is definitely Women Make Film. So many female directors got their work digitized, subtitled and presented as a result of that project. So I'm hoping that with The Story of Documentary Film, it'll have an impact on documentaries. I particularly think of great Egyptian documentaries of the sixties and seventies. So why not start getting it out there?

But it's a big undertaking to try and say, what is the actual history of the documentary? Not what we think it is, but what actually is it? In terms of what have we forgotten, what have we left out?

Anything else coming up now?

I am writing an opera with the great composer Donna McKevitt about baths. I am also working on a novel. Have you ever seen the film Ninotchka with Greta Garbo? It's such a brilliant film. She plays a communist and she sees this hat and she says: “Bring on the revolution. But not yet.” She's in Paris and she just wants a moment of joy. My novel is called Not Yet, and it's about Garbo and that night. I imagine that she escapes from the filming and goes on a trip around the world, and then she comes back to rejoin the film.

So you're currently writing your first opera and a novel?

All art forms are exciting, you know?

Do you plan to venture into feature films? Stockholm, My Love is the closest so far…

Stockholm, My Love is a purely fictional film. Even though people thought it was a documentary. People started to ask the actress Neneh Cherry: What was it like to have killed that guy? But it's all made up!

I'm always interested in the borderline between fiction and documentary, the twilight tone. My Hitchcock portrait is also a fiction film, because he said none of that. It's a sort of imagined radio play about him in a way. And I am Belfast is narrated by a 10,000 year old woman.

I think that people who make pure fiction have an incredible inner world. Which is so creative and magnificent that they want to share it with the public. I don't have that inner world. I'm more like Copernicus. I'm asking: What's out there? What if I'm not the center? The documentary area, lyrical prose or film essay, whatever we call it, is very fertile ground for this kind of thinking. And when you're in a really fertile place, why look elsewhere?

---

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants.