Sun of the Living Dead

I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony,

but chaos, hostility, and murder.

Werner Herzog

This film is about compassion. About compassion for people and nature, and about cultural memory. But what actually is compassion? How long does something remain in memory? We simply sign a petition, and we feel like it’s sorted. I did what I could, and now I think I’ll go order some shoes from another website. I’m not moralising. The question is different – why do some things remain hidden from our field of view even though they’re extremely relevant elsewhere in the world? Aren’t we perhaps beginning to live like a ball on a roulette wheel, jumping from one bit of information to the next? Why has compassion become almost a dirty word? Sun of the Living Dead is simultaneously about pseudo-compassion, mistaken terms, and their meanings.

Prisoners of war from the heroic past, for whom we erected monuments, and contemporary prisoners, for whom we change our Facebook photos. People sentenced to death, whether for crimes they actually committed or in an act of political vengeance. Modern “memorials” after they’ve disappeared from the headlines. Demonstrations that garner interest on social networks and petitions that remain solely in the digital space. These are the subjects Sun of the Living Dead investigates from several different perspectives – the anthropological, the aesthetic, the media, and the visual. It takes the form of a great number of questions and themes, which will be interconnected in a variegated audiovisual collage. The primary axis along which this range of issues will accumulate, through comparisons and analyses, will be the story of a French pilot, which makes a theme both of itself and of our view of it as observers.

Sun of the Living Dead

The issues we attempt to address in our new film seem unrelated at first glance, but they are connected through our reactions to them – our perceptions. Because we are living in the post-media age (as the media endlessly reminds us), our film shows that the world today is chaotic. In this case, intelligibility does not equate to truth. Long ago we ceased speaking of objective evils, and we all know that the media can be a tool of propaganda, or on the contrary can help people come together and initiate change. I’m drawn to the visual as well as the emotional aspects – the things that interest or influence us and why, and conversely, those things which no longer capture our attention.

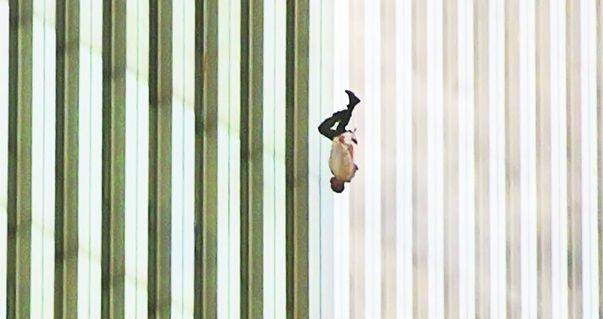

A theme that emerges is that of the ethics of displaying suffering in film and media. Which images, recordings, or documents can we allow ourselves to show and which not? Can we simply pixelate something objectively cruel and unpleasant? Do we react differently to photographs of executions from the turn of the century and those with the same content shot just last year?

Because our film contains so many themes and questions, albeit mutually connected, I prefer the style of a non-linear documentary essay. Ideally this will allow us to answer the questions posed in the film. This film shouldn’t tell anyone’s story. It should instead draw attention to cultural and social phenomena.

Sun of the Living Dead

As is already my custom, the film will be comprised largely of archival footage, for example modern news recordings, internet streams, archives from the beginning of the century, shots from the first and second world wars, interviews, and clips from films, TV series, or other programmes. Some sections will be disproportionately long, while others by contrast will be short. The very viewing of the film should cause discomfort through the perpetual uncertainty it creates regarding what is happening and what twist will come next.

I’m currently in the preparation phase of the film, so from morning till night I sit and watch archives from various newscasts while trying not to die from the sadness concentrated into minute-long reports on the most horrific events of the last twenty years. Of course, we also have to sort out organisational complications or secure access to archival materials, but the thing that troubles me most from the past five years is how I’ve grown desensitised. When you watch endless recordings of the suffering of people you don’t know (and occasionally also people you do know and like), you start to get the feeling that the limits of your sensitivity are shifting and you’re afflicted by a kind of occupational hazard. A recording of a person’s death becomes merely visual material that either is or is not “interesting”. It’s a dilemma I attempt to draw attention to with this new film. I just hope I come out of the battle with “the chaos and hostility of the universe” with minimal losses.

Translated by Brian D. Vondrak