The Archaeology of Artificial Intelligence

The retrospective of computational film highlights works that were developed with methods of creative thinking that we currently use when working with artificial intelligence tools. It also addresses procedures involving recalculations or pre-determined and calculated relationships between individual means of expression, content motifs, or visual and audio components. The program serves as a discursive map, showing how certain forms of thinking and creative practices have shaped our current understanding of AI and its use for creative work.

Our coexistence with artificial intelligences is not only based on the development of technology, but also on approaches that allow us to understand the relationships between different types of sensations, for example between sounds, rhythm, colours, and shapes. The “translation” of sounds into images, colours into rhythm, and shapes into sounds has been going on in the art of the moving image for a century, and it is a fascinating area of creation and exploration. But the programme also explores the technological branch – we will see pioneering films that were made on the first mainframe computers – for example, Olympiad (1971), an animation by Lilian Schwartz, an explorer of computer-based filmmaking in the 1960s and 1970s.

We begin our archaeology of computational filmmaking in the 1920s, when avant-garde filmmakers attempted to evoke rhythm and melody by measuring the length of filmstrips, and planning patterns in the arrangement of pictorial elements – Oskar Fischinger’s Spirals (1926) is one such example.

„The program serves as a discursive map: it shows how certain forms of thinking have shaped the current use of artificial intelligence in creation.“

Works built on the principles of diverse transducers between the various components of film and perception based on visual, sonic, and rhythmic properties are represented, for example, by Music on Triggering Surfaces (1978), in which video artist Peer Bode translates visual parameters of brightness and shades of grey into a sound map.

In her works, animator Mary Ellen Bute experimented with different methods of translating the language of music into a language of abstract shapes, lines, and colours. We see her film Tarantella (1940), on which she collaborated with Norman McLaren. Finnish media artist and electronic music pioneer Erkki Kurenniemi, made Computer Music in the early days of computer-generated music in 1966. Then, in the 1970s, he created a synthesizer that translated the electrical activity of the human brain and the conductivity of the skin into sound.

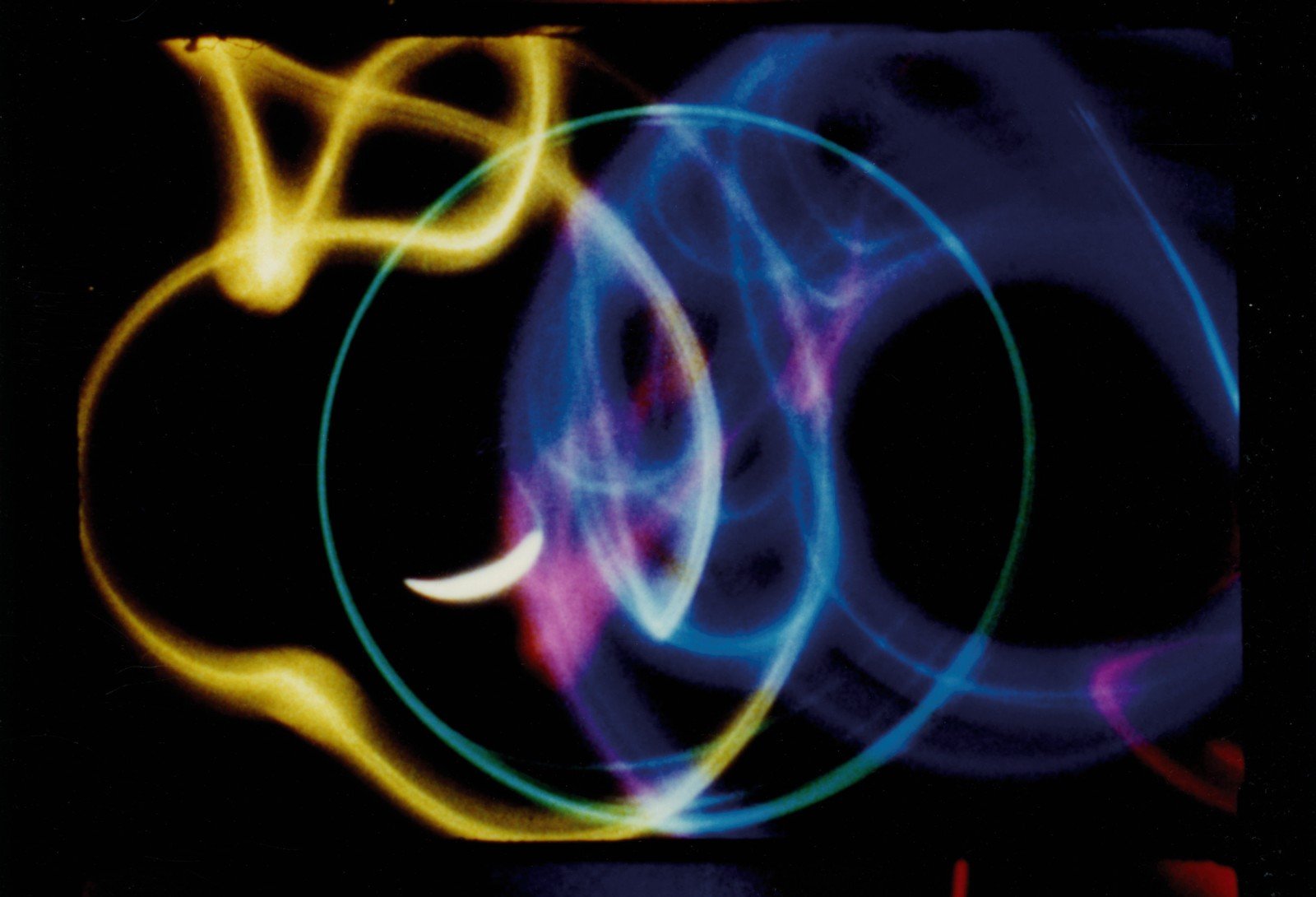

A widespread practice of experimental filmmaking is the creation of scores, maps, precisely calculated or drawn concepts, and plans for future films. For his film #3 (1994), Joost Rekveld created an extensive 13-part score in which he planned the length of exposure, colour, camera position, width of the light track, and speed of camera movements. He then filmed the light, attached to a double pendulum, which provided partly unpredictable angles.

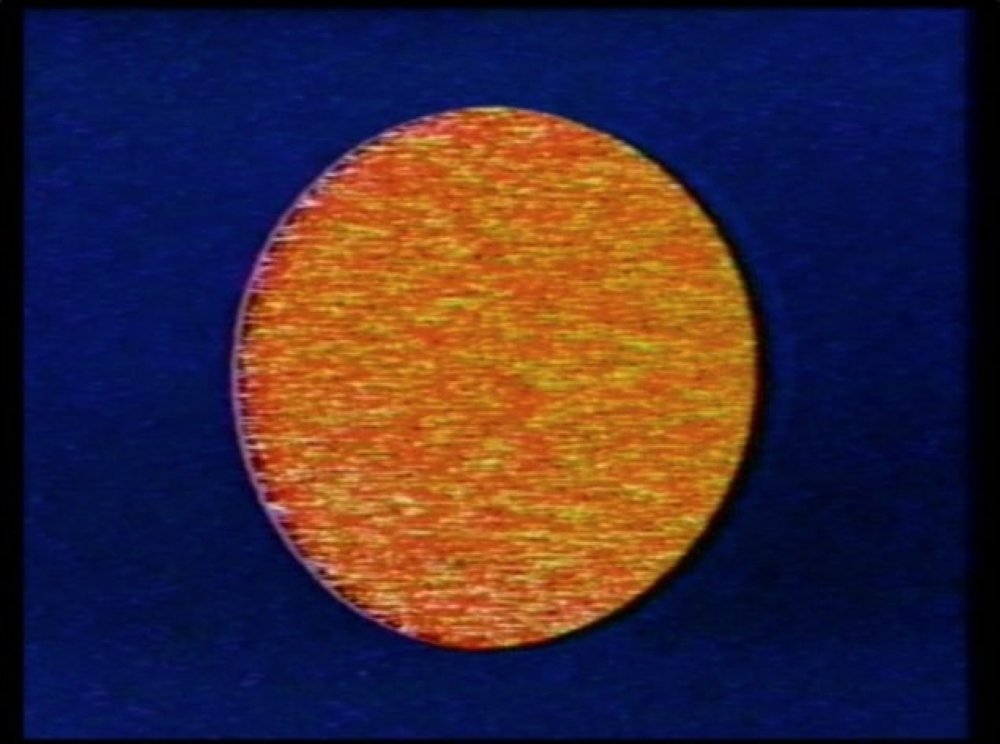

The exploration of various forms of incorporating computers and other devices into filmmaking is evident in the work of Steina and Woody Vasulka (Vasulka is a video artist of Czechoslovakian origin) – we see two of their exploratory video artworks, Evolution (1969) and Noisefields (1974).

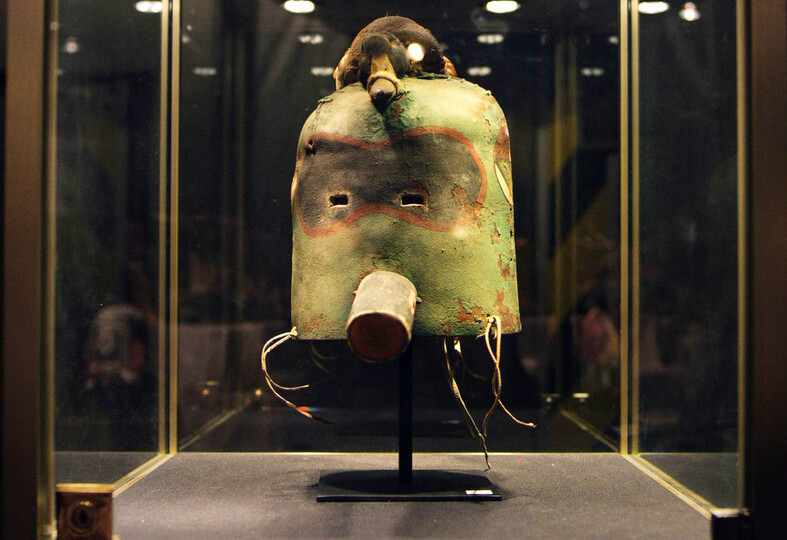

Avant-garde filmmaker, Stan VanDerBeek, who built the audiovisual laboratory for multimedia experiments, and the “experience machine”, Moviedrome, made ten computer films in the 1960s, in collaboration with Ken Knowlton of Bell Laboratories. Poemfield No.1 (1967) is from a series of films made using Knowlton’s Beflix programming language. Poème Électronique (1958) is heard as a soundtrack. It is one of the outcomes of a visual-acoustic immersive event that took place at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels.

The architect Le Corbusier created it in collaboration with Edgar Varèse, who created the electroacoustic composition. James Whitney, a pioneer of cybernetic film, created Lapis (1966), using a mechanical analogue computer as a tool for transformative meditation. Together with his brother John, he became a leading exponent of computer animation.

„Translations of sounds into images, colors into rhythm, and shapes into sounds have been taking place in the art of moving images for a hundred years, and it is a fascinating area of creation.“

From John Whitney we see Permutation (1967), a polyphonic visual composition that makes mathematical structures visible. The playful optical compositions of Spiral (Pierre Rovere, 1984) were co-created by the Canadian video text system, Telidon. For Marc Adriano, the computer he used in the production of Random (1963) was a dream guarantee of perfect randomness – he could explore the possibilities of losing control over the resulting shape, trying to rid the film of traces of authorial intention by making personal and aesthetic interventions impossible.

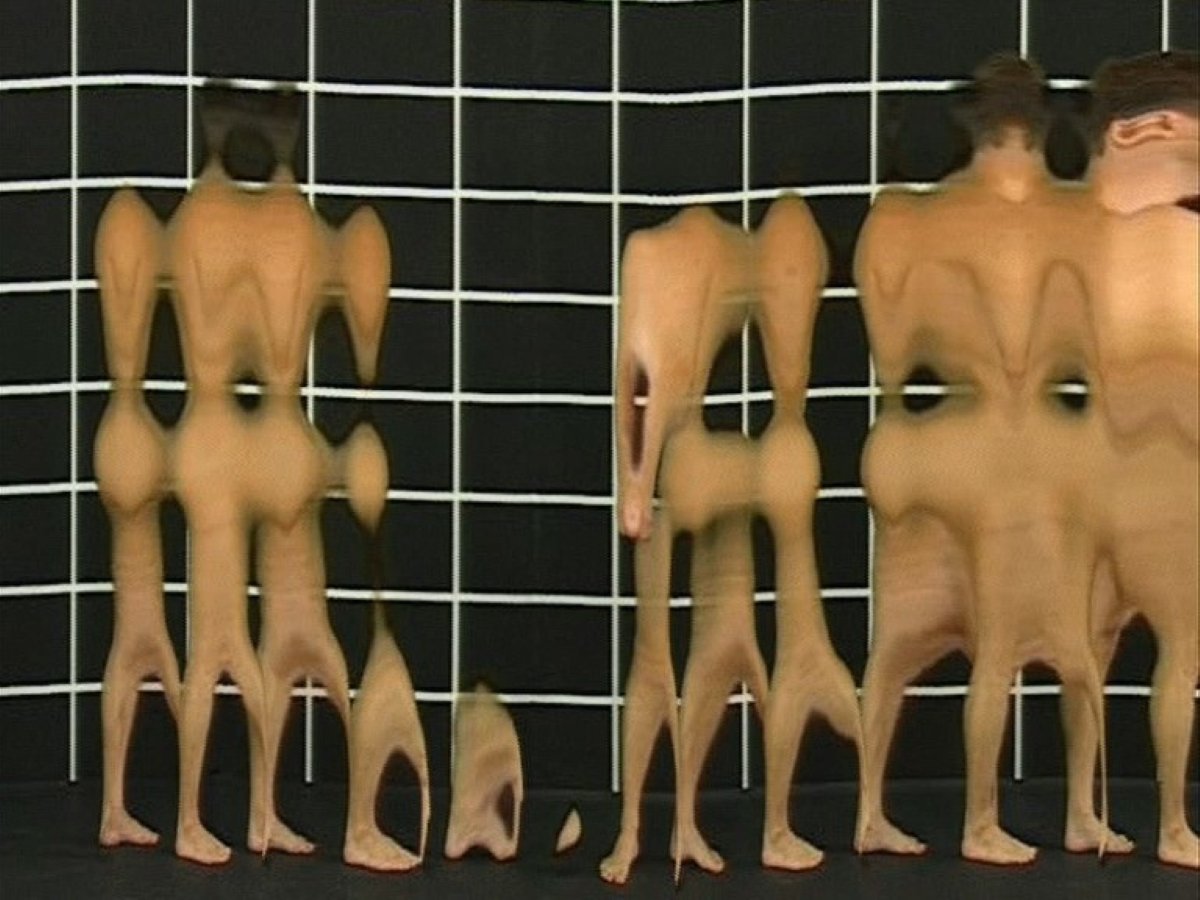

Since the early days of cinema, filmmakers have created devices and systems for capturing and manipulating images and sound. Austrian film technology innovator Martin Reinhart developed the experimental technique of tx-transform. It swaps between a time axis and a single spatial dimension, so that each individual frame shows the entire time of the film, but only a small part of its space. Together with multimedia artist Virgil Widrich, they used this technology to create a film of the same name in 1998, illustrating Einstein’s theory of relativity, as formulated by mathematician, Bertrand Russell.