The engrossing appeal of cinematic engrams

Brazilian director Janaína Nagata makes contact with the past somewhere between affect and internet research in Private Footage (2022). The film, which works with found footage scenes of a South African family in the 1960s, was screened at this year’s FID Marseille. How can her work be interpreted through art historian Aby Warburg’s concept of the engram?

In both of the manifestos of his now famous concept the Theatre of Cruelty, French man of the stage Antonin Artaud criticised film for its rootlessness in relation to the reality it depicts – the form captured on film is fatally detached from its material referent, and the present is thus lost in favour of preserving the past.1) On the contrary, Brazilian director Janaína Nagata’s feature-length debut Private Footage (2022) shows us how thought-provoking the imaginary petrification of time through the power of camera footage can be in the context of cinematic art.

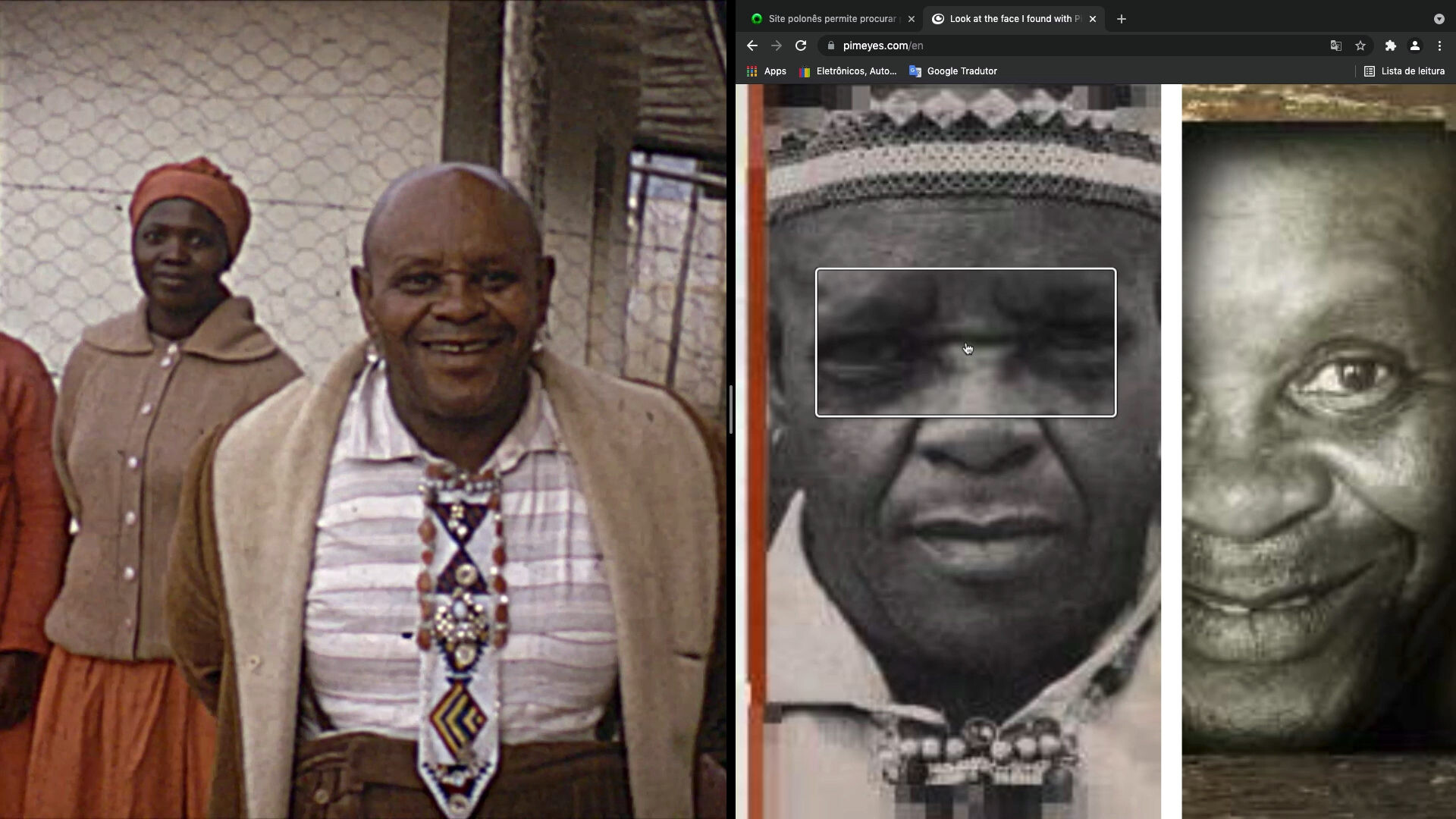

In the scope of experimental film, the term “found footage” is usually used to describe practices in which the author works with already “finished” footage from another filmmaker and manipulates it in various ways, transforming it to fit their own purposes.2) Although Private Footage does not take this route, it could still very well be described as found footage in the literal sense of the phrase, for Janaína Nagata found and purchased an old reel of 16 mm film on the internet with no inkling of its origins. To her surprise, however, the reel did not contain so-called raw material but instead nineteen minutes of rather artfully edited footage dating back to the 1960s depicting various scenes from the life of one South African family. Nagata chose not to meddle with this material in any significant way, introducing it on the screen with just a few written sentences, followed by the nineteen minutes of found footage “in full”. The introductory words here are simply the frame; it is the images themselves that speak directly to the viewer and the artist. It should be noted that the home movie is a fascinating phenomenon in itself, for the person behind the camera does not, as a rule, submit to the coherence and logic of a preconceived concept or fictional narrative when filming but instead records, in a rather intuitive and emotional way, the ephemeral beauty that overflows from the mundanity of their present surroundings and the photogenicity of the things all around them. Nagata is obviously captivated by the compelling power of such images as well; to the sounds of an unsettling musical score – the artist’s solitary, invisible addition to the found material – we watch shots of an entirely observational nature in their original form and original scope: numerous images of the South African wilderness and wildlife as well as events taking place in the city and also more familiar situations, such as short shots of several women by the pool blowing kisses to the camera. Following the denouement of this digitised relic, we see something that is a bit of a media-reflexive trend in videographic criticism,3) evoking a computer desktop exploration of the depths of the internet, which the author has chosen in lieu of an archive as the wellspring of information to help her contextualise the content of the found scenes.

The engram, or Imbuing the present with the past

In order to grasp the aforementioned fascination stemming from contact with images of/from the past, the concept of the “engram” as understood by the German art historian Aby Warburg proves to be crucial. However, if we want to understand the engram better, it is first necessary to take into account Warburg’s concept of the temporality of art history, which is described by Josef Vojvodík in his book Patos v českém umění, poezii a umělecko-estetickém myšlení čtyřicátých let 20. století [Pathos in Czech art, poetry, and aesthetics in the 1940s]. According to Vojvodík, in this context Warburg does not perceive the flow of time as a straight line but rather as a cyclical spiral formed by discontinuous intervals.4)As you can see, according to such thinking, the history of art is interwoven with periodic revivals, the contemporisation of things already seemingly past and extinct, not influenced by causal and chronological development – it would seem that a far greater determinant is the temporal interval bridging “then” and “now” in a moment of temporary unity. It is then the engram that can be seen as a clear-cut example of the catalyst of such an imbuing of the present with the past, a collision triggering the spiral motion of time. These are symbols, memory traces charged at the level of latency with mental energy, and their activation requires contact with the recipient. The extreme impact that results from this contact makes the memory of a certain culture present in the recipient in the form of an affective shock, not a cognition grasped by reason.5) For our purposes, it is significant that in Warburg’s creation of the pictorial atlas Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – a collection of art objects he assembled to represent “[…] the pictorial evidence and visual codes of the physical and mental energy and emotions of humanity”6) – the author used photographs of works of art (such as ancient reliefs),7) not the works of art themselves. Therefore, the loss of the referent through the disconnection of the image from the object being captured – for which Artaud criticised film, as mentioned above – is clearly not in any way indicative of an engrammatic effect, and if photography can affect the recipient in this way, why not film? The latter, after all, is probably even more suitably predisposed to the preservation of time and to its subsequent contemporisation. As André Bazin points out in his essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image”, photography embalms time, thus preventing its destructive effect, while film goes even further in this respect, for in this embalming it also preserves the image of things in its very dynamic duration.8) By contrast, in photography there is, in the words of Roland Barthes, “an enigmatic point of inactuality, a strange stasis, the stasis of an arrest.”9) It would be clumsy, however, to reduce film to a mere time capsule, for the added value of photogenicity cannot be overlooked. The images of the objects and subjects captured, in addition to their imaginary liberation from the flow of time, also acquire new visual qualities, and therefore we do not deviate from the field of art history as much as it might seem at first sight.

A quasi-nostalgia for something we ourselves did not experience

The zeitgeist made manifest by the moving images of the found material in Private Footage thus serves as an engrossing prelude for the audience and the filmmaker, conditioning the affective contact with the erstwhile milieu of South Africa; however, as already noted above, Nagata also decided to incorporate into her work an epistemic approach that contrasts somewhat with this poetic sensibility. To these photogenic images on old, faded analogue film, which trigger a kind of hard-to-grasp quasi-nostalgia for moments we did not experience ourselves and places we have not been, the filmmaker has appended a postscript in the form of an internet search for context regarding the place and time the images were captured. She thus hovers somewhere between two difficult to reconcile ways of knowing: the affective impact of the images themselves, evoking abstract impressions and an entirely emotional response, and the rational effort to bring more concrete information into the situation after said impact has been felt. The filmmaker herself is obviously aware of this contrast because the outline of her work is precisely “split” to fit this pair of epistemic approaches. However, Nagata’s choice to use the internet as the sole tool in her investigation seems to result in there being no clear starting point in the space after the engrammatic impact of the images of the past. Her interaction with this medium is fairly unpredictable and could easily be likened to a situation experienced by probably every internet user – fascinated by a particular phenomenon, she gets caught in that familiar loop of vastly divergent Googling in which, in her own immersion, she examines the phenomenon from all possible sides, exploring one link after another but never arriving at a clear or definitive result.

All the same, despite its follow-up investigation, Private Footage is not a kind of “film à thèse”. While the filmmaker’s scouring of the internet has a foundation on which the information she finds is amassed – namely a specific space-time connected with the origin of the footage – the trajectory of her research often seems rather random and associative. We are thus presented with a broad range of disparate information – from the circumstances of apartheid in South Africa to the form of contemporary family vlogs on YouTube. Moreover, it is not clear where exactly the filmmaker is going with her actions as her work is very stingy with regard to the sharing of information that prefigures the direction of development. The search here is distracted and playful rather than focused and didactic. The question arises as to whether Nagata, in this second part of Private Footage, wanted to present her own authentic process of cooperation with the internet, the outcome of which was not clear in advance, even to her. This would be something similar to the fascination described above, which is familiar to the vast majority of internet users, rather than an attempt to create a strictly expository documentary that goes from point A to point B. For that matter, it is interesting that it was in the online space that Nagata found and purchased the engrammatic footage presented here, and so no matter how much its effect may create the impression of a rediscovery of a time gone by, it also comprises a mere step away from the artist’s activities on the internet, where her journey in creating Private Footage both began and ended.

---

Notes

1) ARNAUD, Antonin. The Theater and Its Double. New York: Grove Press 1958, p. 98–99, further p. 125–126.

2) See, for example, ČIHÁK, Martin. Ponorná řeka kinematografie. Prague: Akademie múzických umění 2013, p. 171–176.

3) For more, see: ANGER, Jiří. Cinefilie ve věku algoritmů: Úvod do současné videografické kritiky. Film a doba 67, 2021, no. 4, p. 9. In Anger’s words: “In short, these are audiovisual essays that simulate the everyday experience of a PC or smartphone user, specifically their movement across a computer or mobile desktop interface” (ibid., p. 9).

4) VOJVODÍK, Josef, WARBURG, Aby: „Formule patosu“ jako „psychologické dějiny meziprostoru mezi pohnutkou a jednáním“. In: LANGEROVÁ, Marie – VOJVODÍK, Josef. Patos v českém umění, poezii a umělecko-estetickém myšlení čtyřicátých let 20. století. Prague: Argo 2014, p. 71–72.

5) Ibid., p. 76.

6) Ibid., p. 67.

7) Ibid., p. 67.

8) BAZIN, André. The Ontology of the Photographic Image. Film Quarterly 13, 1960, no. 4, p. 4–9.

9) BARTHES, Roland. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang 1996, p. 91.

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants 2014–2021.