Topics, media and documentary 2.0

To (Dis)own One's Own Image: The Slovak Retrospective at the 28th Ji.hlava IDFF

The value of retrospectives at film festivals lies not only in re-evaluating older material but also in reconsidering the existing narratives surrounding it. Curated by art historian Petra Hanáková for the 28th Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, the selection "We Have Our Own Film! Images of the Slovak State" featured 24 films made during the former Slovak State (1939-1946) or in the immediate aftermath of its collapse.

Foundational to the retrospective, Hanáková's book Máme svoj film! Slovenská filmová kultúra a propaganda 1939 – 1945 (translated as We Have Our Own Film! Slovak Film Culture and Propaganda 1939-1945), published by the Slovak Film Institute in 2024, is the first independent monograph examining Slovak film culture during the former Slovak State, still colloquially known as the First Slovak Republic.

The author's research, also reflected in her work in Jihlava, examines the broader context of film production and reception, positioning cinema as a strategic tool of political propaganda in diverse political contexts. Due to the retrospective's scope, I will focus on its overall intention and importance. I will highlight its selected aspects, while acknowledging the impossibility of honoring all the rich details characterizing individual films.

What was The Slovak State?

The Slovak State, though nominally the first independent Slovak state in history, was a clerical fascist puppet state of Nazi Germany. It was established with German support for Slovak independence from Czechoslovakia. Six months earlier, Germany had occupied the Sudetenland, the Czech lands largely inhabited by a German population. Indebted to Germany, the new Slovak State was forced to cede portions of its territory to Hungary that same year. It also participated in the German attack on Poland, sent its army to the Eastern Front to fight the Soviet Union, and copied the Nazi leadership model. The head of the state was President Josef Tiso, a Catholic priest who assumed the title Vodca ("Leader").

With the support of German troops, the authorities of the Slovak State were responsible for the deportation of more than 70,000 Jews to labor, concentration, and in effect, extermination camps. Of this number, more than 57,000 Jewish residents were deported by Slovak authorities themselves. Only a minimal number survived the war. From 1939 to 1945, the Czechoslovak government operated in exile. In 1944, united anti-fascist forces launched the Slovak National Uprising. After the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945, the Czechoslovak Republic was restored. With the rise of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and following the Yalta Conference, the country ultimately fell into the Soviet sphere of influence.

"Hanáková's retrospective underscores how the authorities of the Slovak State, as well as the voices empowered after its dissolution, were acutely aware of the potential of propaganda in this process."

Unsurprisingly, politics played a pivotal role in shaping film production and distribution within Slovak territory. As part of the highly centralized Czechoslovakia, Slovakia adhered to the directives set in Prague. In terms of both economic and cultural development, it lagged behind the Czech portion of the country. Hanáková explained to the audience at her retrospective that this discrepancy meant Slovak themes, language, and actors only began to appear in Czechoslovak films in 1935, marking the true beginning of Slovak cinema. In the cultural realm, as in others, the central aim since then had been to grant Slovakia greater autonomy. However, the country was still far from modernized, remaining poorly industrialized and even lacking widespread electrification. State investment was crucial for the development of cinema, an inherently expensive and conceptually intricate endeavor.

Hanáková's retrospective underscores how the authorities of the Slovak State, as well as the voices empowered after its dissolution, were acutely aware of the potential of propaganda in this process. Until 1939, Slovak audiences were largely passive consumers of foreign cinema, whereas the Czech part of Czechoslovakia boasted a decades-long tradition of film production. All of this set the stage for the reimagining of Slovakia on the big screen, represented through carefully curated images served to its own people.

The rise of Slovak cinema

As Hanáková emphasized in her introduction of the retrospective in Jihlava, Slovak society today still grapples with an ambiguous relationship to its complex past. The question of who should be regarded as the occupier and who as the liberator remains unresolved, a dilemma that this is intriguingly reflected in the diversity of films included in the retrospective. In 1939, the joint-stock company Nástup was established, a monopolist on the film industry market. Its films are central to Hanáková's retrospective, as well as how they were repurposed after the fall of Tiso's regime. One of the company's first productions was an eponymous film weekly, closely monitored by the Office of Propaganda. The Slovak-German agreement dictated that all development in Slovakia had to be aligned with Germany's interest. The Nástup weekly reflected what the government wanted the public to see or, better yet, to conceal (e.g. mass deportations). Much of the content incorporated into the weeklies was sourced directly from Germany.

The primary objective of the weekly was to legitimize the regime. Typically, they were compilations of documentary material drawn from various sources, with no mention of specific directors. However, this does not mean that the editors of the individual sequences remain unknown. Author films also convey positive messages about the state of workers (Pal'o Bielik's 1942 For the Health of a Worker), the quality of education (Eugen Mateička's 1943 Library of the Slovak University, which highlights how, despite the University of Bratislava's existence since 1919, the Slovak State actively Slovakized it), modernization (Viktor Kubal's 1944 animated short The Mysterious Old Man, which illustrates the process of electrification), industry (Bielk's Our Daily Bread and Artificial Fibres, along with Mateička's We Produce Glycerin, all produced in 1943), and the utilization of natural resources in Slovakia (Bielik's 1942 Travertine–The Slovak Marble).

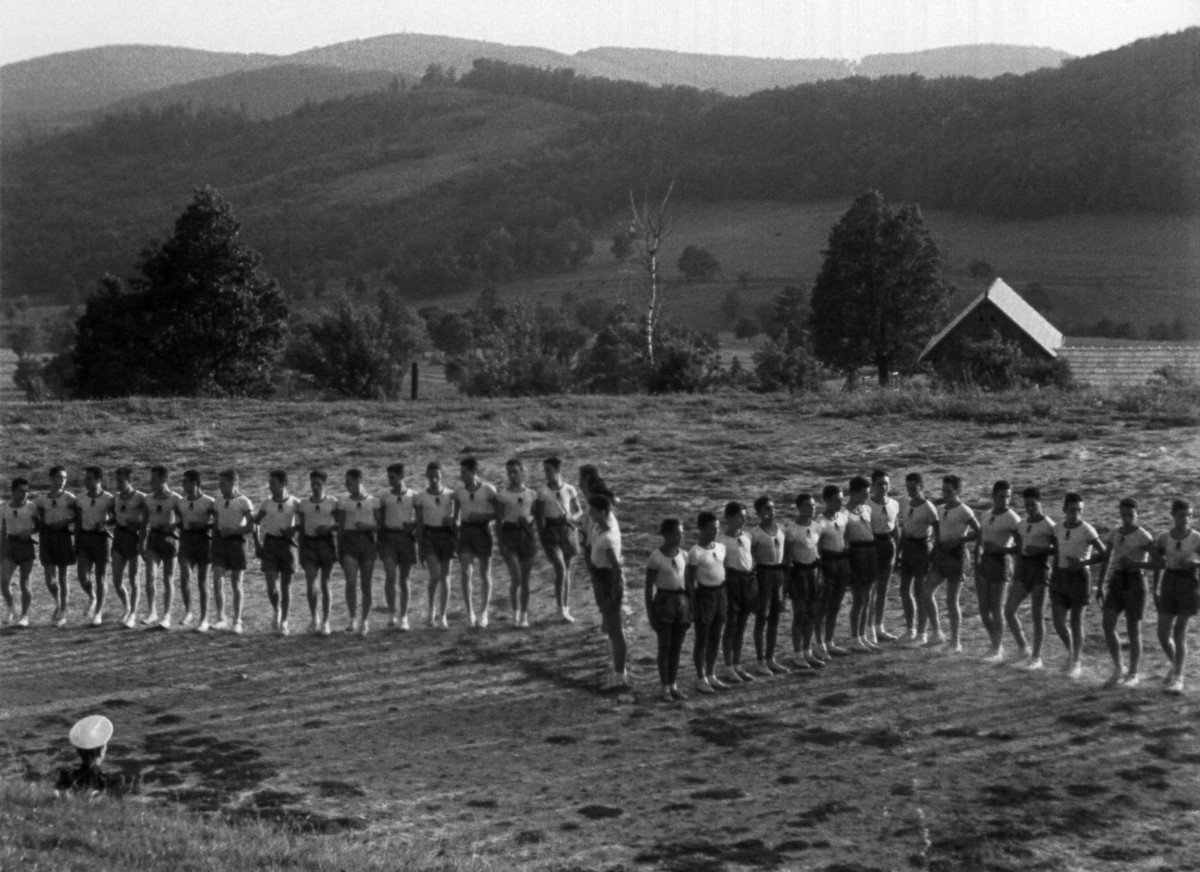

The sense of pride was instilled in the people through sequences that honored the contributions of the Slovak army on the Eastern Front (Ivan Július Kovačevič's 1942 From the Tatras to the Sea of Azov) or celebrated the healthy, capable bodies of the Slovak youth (Bielik's 1942 In the HM-GIL Camp, the camp being a joint venture between Slovakia and Italy). All Nástup films exhibit swift editing techniques characteristic of contemporary newsreels, where moving images are accompanied by a narrator's voice and/or background music. The propaganda within these films stems not only from the specific subjects they address but also from how topics are treated. The narration guides the audience in unmistakable directions of interpretation, suppressing any critical engagement with the material presented. Frequent are the demonstrations of the state’s power and righteousness, an apparently comfortable bourgeois public life–including one tied to the Catholic Church–and the nation’s competitive spirit. In one of the weeklies, it is suggested that “not even Anglo-American terror can break their [Slovak] faith in victory,” as images of a sports tournament accompany the spoken observation (Nástup 295 A/1944). The narrator references the bombing of the Apollo refinery in Bratislava, which had been confiscated by the German IG Farben at the time, carried out by the Allies. The factory was selected as a military target because it produced gasoline for the Third Reich.

Not only propaganda

Poetic or even spiritual qualities come forth in films such as Kovačevič's 1940 Permanent Lights and Mateička's 1943 Summer under the Kriváň Mountain. In the former, the nation's "great men" are urged to stand up for themselves and build the life they have always dreamed of. In the latter, women are depicted mowing meadows with scythes. Both films possess significant ethnographic and anthropological qualities, including society's patriarchal disposition, where male efforts "create history," while those of women are more closely associated with service-oriented work. The Slovak people are also portrayed as deeply connected to the land, both in terms of its cultivation and the mythical, transcendent qualities it represents. This portrayal is an extension of the German Blut und Boden cult ("blood and soil"), which idealized peasantry, dilligent physical labor, and racial superiority.

In a different manner, a similar sentiment is conveyed in Bielik’s 1942 Disappearing Romance, a documentary study of the traditional making of shepherd’s axes. The premodern craft is not only appreciated but romanticized, despite its contrast to the vision of a great national industry reliant on large-scale production. Alongside these favorable depictions of folk customs, patriotism is fostered through picturesque portrayals of the Slovak lands. Mateička’s 1942 On the Locomotive takes the audience on a scenic train ride from Bratislava to the Tatra Mountains. This is not only a film that poeticizes the Slovak landscape but also celebrates the efficiency of Slovak railways. Bielik’s 1942 There Once Was…, on the other hand, transposes the love for one’s country into the realm of dream and imagination. A mother is telling a story to a child beside a wooden cradle. The boy enters the rich world of the Spiš castle, where he battles enemies to defend the territory.

After war

After 1945, anti-fascist films sought to introduce audiences to the new post-war reality. Some od the film workers themselves had participated in the Uprising. Optimism permeats Ján Kadár's 1945 Life Grows on Ruins, an enthusiastic depiction of the renewal of the infrastructure and the spirit of society. Central to the narrative is the reconstruction of a bridge, designed to withstand the passage of a freight train. The film not only showcases the people's labor but also their innocent joy once the train successfully crosses the newly functional bridge. Scenes of a jubilant, victorious collective body contrast with earlier depictions of the devastated countryside. The earliest film to offer a relatively balanced view of the war, Bielik's 1946 For Freedom incorporates materials about the Uprising from various sources. It shows people's direct experience of mobilization, detailing life within partisan units. Germany's growing influence over Slovakia is symbolized by a claw casting a dark shadow and reaching for territory on a map.

Other films are more concerned with enemies. Kadár's 1946 They Are Personally Responsible for Crimes against Humanity! was compiled from wartime weeklies and screened while Tiso's administration was still in court awaiting its verdict. The power of montage is evident in the deliberate use of imagery from the fallen regime, repurposed and critically interpreted, such as that of the parade of Hlinka's Youth. Kadár's another 1946 work, They Are Personally Responsible for Treason of the National Uprising!, delves into the political background of the Uprising, exploring its significance for those involved, and illustrating it on maps. In contrast, Kubal's 1946 May We Live in Peace deals with the resettlement of populations in southern Slovakia, showing how markers of Slovak identity–public inscriptions in Slovak, for example–replaced those of Hungarian presence. The film also provides factual information about Slovak-Hungarian relations at the time.

Relationship to the representation of reality

Finally, this Ji.hlava IDFF retrospective underscores the universal importance of propaganda in securing popular consent. With recent insights into the circumstances shaping film culture of the time, it demonstrates how various political entities could share a vested interest in controlling the public image of their respective causes, whether morally justified or not. Hanáková's research also reveals the widespread practice of repurposing existing archival material to convey a message different from the original intent. This approach is evident in other contexts of regime changes as well (for example, in the film heritage of countries like Croatia, whose history shares certain parallels with Slovakia's, though such comparisons must be made cautiously).

Ultimately, the case of late-1930s to mid-1940s propaganda films in Slovakia points to the complex professional paths of the creative class active under oppressive regimes. How much did film workers need to compromise, and in what specific instances, especially given that many continued to work after the change of government, pursuing different goals and shared messages? We Have Our Own Film! Images of the Slovak State offers a wealth of insights into a troubled country's history and its concern about representation, as well as serving as evidence that propaganda remains both an aesthetic and ethical issue to which no social order is entirely immune. Investing in programs like this to enhance audiences' media literacy is crucial for cultivating the perspicacity necessary for a thriving democratic culture at all times.

---

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants.