Why Series Suck

Laura Palmer’s promise from the end of Season 2 of Twin Peaks, “I will see you again in 25 years,” must have been the longest cliffhanger ever! After the first ten minutes of Twin Peaks Season 3, one might almost hope that Lynch could succeed in weeding from the audience most ‘quality TV’ afficionados. They showcase a slow, repetitive, intricately staged routine. A mysterious, empty suite of rooms in a New York highrise houses a weirdly retrofuture glass-walled chamber with an opening towards the outside. At specific intervals, a camera? takes photos? of its inside, which an operator then stores in an equally retrofuture archival machine. A threat of alien life seems to pervade alongside an agent Cooper who, since invaded by Bob in the final scenes of Season 2, has become an evil force comparable to Chigurh in Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for old Men or Lorne Malvo from the TV series Fargo.

Without going further into the beginning of Season 3, much of which takes place in the Red Room we know from the first two seasons, what is it that separates Twin Peaks from the gros of quality TV series? And what are quality TV series in the first place?

From a media studies perspective, quality TV series are hybrids between ´traditional´cinema and ´traditional´ TV. From a vantage point of post-cinema, such series assume a ´cinematic quality´ by way of immense budgets and ‘big production’ logic. A TV studies viewpoint recognises the positioning of these platforms in ‘real life’ on the new digital media landscape comprised of TVs, computers and smartphones rather than a time- and site specific experience in a traditional theater.

If this positioning is interesting in terms of TV series allowing, for instance, binge-watching, a way of viewing that was impossible in the time-specific universe of TV but that began once VCRs were added to the media landscape, what is less interesting is their mode of production, which combines that of mainstream Hollywood cinema and of regular, old-fashioned TV.

TV series are still produced according to a TV format, which implies ‘writing rooms,’ ‘show runners’ and a general bundling of expertise that creates a weirdly uberclever, transpersonal milieu in which, speaking metaphorically, a single artistic handwriting – not that there ever was one in mainstream Hollywood cinema – is replaced by beautiful, shiny fonts. Also, like mainstream cinema, quality TV series still transport well-rehearsed ideologies in their faux-subversive narratives. Of course in Fargo, the enemy comes from without, while in Twin Peaks the enemy comes from within us all.

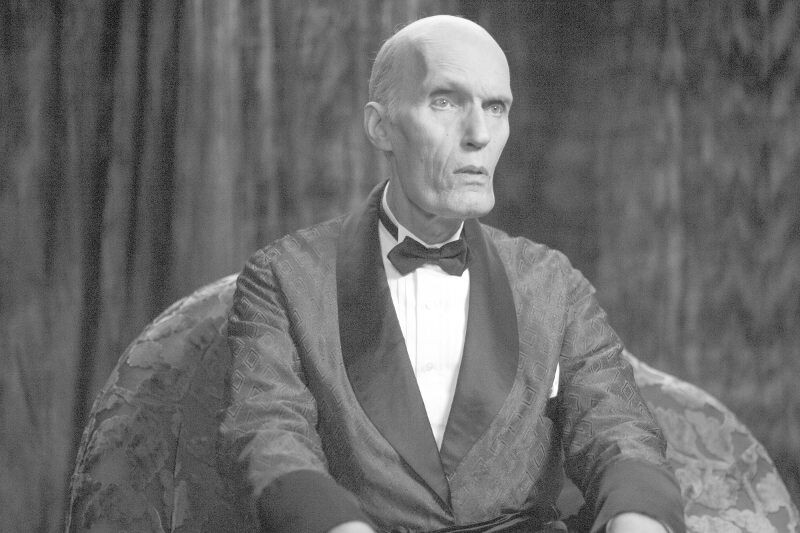

Twin Peaks (photo: Suzanne Tenner)

By default, we think of quality TV as fiction TV. Apart from the highly publicized quality TV series that make up the bulk of what used to be, before the ubiquitous time-axis manipulation of today, ‘prime-time’ TV, there are series that often go ‘under the public radar’. Very often these are historical documentaries, PBS material, that is, or docu-fiction TV, such as Roots, which is to ‘documentary TV’ as Twin Peaks is to fiction TV. According to our friend Victor Wloch, who knows these things much better than we do, some of the better series are John Adams, Book of Negroes, Hatsfields and McCoys, This is England 86, Holocaust, Show me a Hero, or The Corner, which, before The Wire, brought realism to American TV. If these series do good, serious historical reconstruction, more power to them!

The difficulty, however, is that most of the time ‘the documentary’ has been subsumed into elaborate mise-en-scène. Today, the faithful recreation of the visual milieu of a specific period as well as, in the better cases, of its manners, is enough to give fiction TV the allure of being a ‘documentary.’ Boardwalk Empire is an example of this trend, as is The Borgias. One might fear that even The Game of Thrones would be considered by some viewers to be a documentary. Now, docu-fiction tends to transport ideology by way of its seamless documentary simulation of a specific period or event. In that sense, it is a bit like ‘fake news.’ It simulates history, but from within a fundamentally ahistorical point of view. As such, it does all that a documentary would not want to to. In this context, the question of the documentary is spanned out between PBS and Mad Men. We will come back to this at the end.

What we won’t find in quality TV is ‘independent TV,’ as in ‘independent cinema.’ This loss of ‘independence is, in fact, the price we pay for the success of quality TV. To be sure, there are some ‘independent’ TV series, but they are few and far-between. Twin Peaks, the primal scene of all quality TV was, as was, more recently, Louis C.K.’s Horace and Pete. Quality TV was important in terms of TV history such as the introduction of realism by The Wire, the opening up of TV to the visualization of taboo-topics, made possible by the implementation of payTV, and the updating of a ‘local colour’ sentiment and poetics in, say, Fargo. Years on, however, a general ‘predictability of unpredictability’ has emerged, as well as a ‘careful,’ and often exploitative treatment of taboos. One does not know which of these two treatments is worse.

From within different parameters, quality TV transposes the poetics of postmodernism, with a big budget no less, onto the high definition TV screen that now is as big as a ‘small cinema.’ It is a sadly tame postmodernism, however, which should allow for the impossible. While literary postmodernism was for the elites, and difficult to read, the new TV-postmodernism is a popular format that is at the same time intelligent. It is self-reflexive, smart and at the same time visually and productively opulent. Also, it is situated in a media landscape that has multiple and easily accessible entry points, such as blogs, fansites and other producer-consumer interfaces.

In his 1987 book Television Culture, John Fiske has, at a time when ‘quality TV series’ were not yet as ‘intensely quality TV’ as they are today, proposed the term ‘the producerly’ to herald this becoming-producer of the consumer taking place, more and more, on these digital interfaces, which allow inceasingly easy entries of consumers into the universe of production. On the new digital platforms it is much easier to interface with the producers by developing new plotlines, or by proposing alternative narrative pathways, as well as by discussing various aspects of the respective series. It is symptomatic, however, that the new reader-producers write books such as Fifty Shades of Grey, Roland Barthes, whose differentiation between readerly and writerly texts makes up Fiske’s conceptual backdrop, would no doubt be shocked and dismayed.

The Wire

In ‘the readerly,’ Barthes notes in S/Z1), “everything holds together, everything must hold together as well as possible” (181). In other words, the readerly network of signs is tightly crocheted and ”the discourse scrupulously keeps within a circle of solidarities” (156). One such solidarity is the solidarity of logic, which means, in terms of narrative, the solidarity of cause and effect: “The moral law, the law of value of the readerly, is to fill in the chains of causality “(181). One might say that the overall project of the readerly text is the artful assemblage of architectures of the signified: “in this text nothing is ever lost: meaning recuperates everything.”

In the critical reception of Barthes’ concept, readerly texts have often been identified as ‘easy texts’ because they provide closure. They cater openly and gladly to our assumed reading practices and expectations. Readerly texts, however, at least the best of them, are not at all easy. What Barthes calls them is “serious”(4) in the sense that their reading implies operations of ‘understanding.’ The readerly creates readers who practice circumspect, often arduous acts of hermeneutics and exegesis.

If ‘readerly’ texts are often considered easy texts, ‘writerly’ texts are often understood as difficult. They are taken to be immensely complex, and, unnlike quality TV, not pleasurable, a.k.a. easy to read because they make the retrieval of meaning difficult. This distinction, however, is not all that Barthes’ distinction is about. In fact, if readerly texts are often not easy, perhaps writerly texts are often not difficult.

When Barthes notes that the writerly calls to the reader to participate actively in the production of the text, for instance, this does not mean that the writerly texts asks of the reader to actively work for the creation of meaning, but that the reader should participate in the delight of creativity and of the creative act. The writerly text concerns a ‘revolutionary’ bliss that unhinges the political economy between writer and reader, “the pitiless divorce which the literary institution maintains between the producer of the text and its user, between its owner and its customer, between its author and its reader” (4).

In fact, Barthes sets up an immensely difficult asymmetry. While readerly texts can be found in books, writerly texts are not even texts. “[T]he writerly text is not a thing, we would have a hard time finding it in a bookstore. […] The writerly text is a perpetual present.” It is paradox. It is a constant, dynamic practice without ‘reification.’ (5). “[T]he writerly text is ourselves writing, before the infinite play of the world (the world as function) is traversed, intersected, stopped, plasticized by some singular system (Ideology, Genus, Criticism) which reduces the plurality of entrances, the opening of networks, the infinity of languages.” The writerly, then, denotes the pure potentiality of every text to share and embody the given multiplicity of the world. The world in and of pure play. While the readerly highlights the signified, the writerly text is us ‘reading’ the world as a multiplicity of ‘pure signifiers.’ It concerns not a structure but “a galaxy of signifiers, not a structure of signifieds” (5) It is an “absolutely plural text. (5-6).

The writerly, then, is the text of the signifier before that signifier is tied to a signified. To ‘its’ meaning, that is. It is the text of sound, one might say, or of the splendour of what Jacques Lacan has called the ‘stupidity [betise] of the signifier’ as set against the serious cleverness of the readerly. What the writerly really means is leagues away from the dissemination of meaning across as many media platforms as possible that sustains today’s TV franchises. It means to produce, ‘on top of’ the readerly text, or, ‘while reading the readerly text,’ the pure enjoyment of the signifier as expressing the multiplicity and plurality of the world.

The writerly has often been read as the ‘postmodern text.’ And although some postmodern texts enact the dissolution of meaning – not its centrifugal dissemination! – and set the signifier against the retrieval of the signified in popular texts, their often self-aware intricacy, for instance, does not per se qualify them as ‘writerly.’

It is precisely at this point that John Fiske’s term intervenes. Taking the readerly to be the simple, popular text and the writerly to be the avant-garde, difficult, postmodern text, Fiske finds in ‘good’ TV series the best of both worlds. TV texts are popular and still they turn the viewer into an active participant in the production. Thus: the ‘producerly.’ If the writerly is difficult and activating, the producerly is popular and activating. Translated into today’s terminology: quality TV is writerly and we still like to watch it. If TV is ‘readerly or watchable,’ quality TV is ‘writerly or filmable,’ the simple story goes.

Actually, in their investment in meaning and its fetishisms, what Fiske calls the producerly is situated deeply within the realm of the readerly. None of the elisions and gaps built into quality TV series celebrate ambiguity and the loss of meaning. All they do is create the room and desire for narrative extensions that provide missing pieces in further texts that float across media platforms and as such activate both an even deeper desire for meaning and an even stronger investment in the franchise. Ultimately, Fiske’s producerly text is nothing but a cover for the relentless commodification operative in the economy of the readerly. By way of the producerly, texts are inserted into the both additive and addictive logic of ‘seriality’ – why series suck and ‘suck you in’) - for purposes of commodification. They are something quite hellish, in fact. They are ‘productions of consumption.’

Game of Thrones (source: HBO)

The writerly, as a mode of reading, is reading joyously. It is reading in the mode of polymorphous perversion. It does not imply the supercharging of meaning. Rather, it celebrates the subtractions of meaning in the text and the gain of intensity. It celebrates writing becoming multiplicity. It asks, in other words, for a specific sensibility of reading. It celebrates the surprising newness of every sentence, which makes the overall problematics, by the way, not at all a question of genre or of high versus low culture because there are complex thrillers and simple sonnets, surprising melodramas and predictable tragedies.

The audience of the writerly is not the academics, but people who enjoy the dissolution of meaning into intensity. It consists of connoisseurs of individual handwritings, of spectacles of ambiguity and the loss of narrative control. We will see how ‘independent’ Twin Peaks will turn out to be. Remember that initially, Lynch and Frost planned not to provide any explanation for the murder of Laura Palmer.

A final word of caution: in a universe in which a trash TV star is president, we need to analyze trash TV, the dark underbelly of quality TV. Today a middle ground has ceased to exist. While quality TV is for the bourgeoisie, trash TV, in its enactment of a new and scary social logic, makes up the cultural noise that surrounds us. Here we have the other side of the documentary. If one side is bourgeoise docu-fiction, the other is docu-trash. This, of course, is even worse. Consider all the formats in which ‘real-life’ situations are played out by way of a ‘loosely scripted life.’ Most of reality TV works like that. In a realm somewhere between script and life, but fundamentally fake. Nothing in reality TV is truly, seriously documentary, because the complete real-life event is pervaded by the logics of spectacle on the one side, and of an envious voyeurism (where the documentary concerns ‘stars’ such as the Kardashians) or a cruel voyeurism on the other (where the documentary concerns various forms of ‘trash-reality’). Such is the same voyeurism that the plethora of cooking, talent and other reality TV shows that ‘test’ candidates rely upon. Just watch, if you do not do so already, the elaborately drawn out moments of judgement of candidates that we have been conditioned to ‘perversely enjoy’ and tell us that we’re wrong!

Today, the field of ‘the documentary’ is in danger of either being entirely subsumed by quality TV mise-en-scène, for instance via Mad Men’s careful recreations of 1950 and ‘60s culture, or equally carefully simulated in reality TV’s claim to ‘every-day life authenticity.’ In-between the Scylla of quality TV and the Charybdis of reality-TV, the documentary, an important, complex form of art, must find its course in today’s turbulent medial waters. Today, more than ever, we need careful, serious, dare we say ‘independent’ documentaries that set their both analytical and loving gazes against a culture whose gaze is both ‘lost in quality’ and ‘lost in trash:’ two sides of the same cultural coin.

Notes:

1) BARTHES, Roland. (2007). S/Z. New York: Hill and Wang