We have our own film! Images of the Slovak state

In four collections, this section presents a representative selection of period production. Two selections of cultural films complement the characteristic previews from the weeklies. The other two collections represent, on the one hand, a pair of films in which I. J. Kovačević participated as a director or editor, and on the other hand, a post-war “reckoning”," and a critical image of the Slovak state in the second half of the 1940s.

The cinematography of the Slovak state is relatively well-charted in Slovakia - partly because the volume of films is not large - but also because it is rarely the object of critical self-reflection. Or even of some broader social debate. It is related, on the one hand, to the still-unnegotiated relationship of the Slovaks to their wartime Slovak statehood, and on the other hand to the insufficient distancing of the current, second statehood from the fascist content of the first one. As with the uprising, the Slovak state is still politically “bargained” and negotiated. Especially today, when the word ‘fascism’ takes on a distinctly performative content, and a fascist is often referred to by neo-fascists as an anti-fascist, based on the principle of “A thief shouts ‘catch that thief’”.

Perhaps also in this context it is important to remember in the Czech environment that the Slovak state, although it was created under duress and under the protection of the Third Reich, was not in fact a protectorate! The harshness of the regime, even considering its different character, was different, and the practices/strategies of collaboration and resistance were different. I emphasize this because Czech historiography sometimes tends to evaluate the Slovak state and its culture through a protectorate prism, and therefore often misses the point, creating unnecessary irritation on the Slovak side.

In the Slovak state, and especially in its cultural environment, the situation was often more complicated, where many cultural workers worked “under both regimes”, so to speak, both in the establishment, and in the resistance. In other words: as if the protectorate equation of the rebellious Bohemia versus the German occupier did not apply here. The work of many “collaborators” (see Slovak national economists) was not about legitimizing the regime, but rather about its transformation or destruction from within. I mention this also because the Slovak cultural situation today is beginning to resemble the fascist one, and a part of the cultural community will probably soon choose a similar strategy.

But about the film: In 1939, the monopoly joint-stock company “Nástup” was created, on the initiative of some people connected with Tatrabanka official, Pavel Čambala, and with the participation of the state, two banks, and the Deutsche Partei. One of the first products of the monopolizing film industry was at the end of 1938, the film weekly “Nástup”. The weekly, monitored by the Office of Propaganda, initially had a contract with Aktualita, and later, under the new regime, with UFA, from which it received most of its contributions. What was new, however, were their own film shots – ranging from one to three reports, which formed the mandatory 20 percent of the weekly’s content.

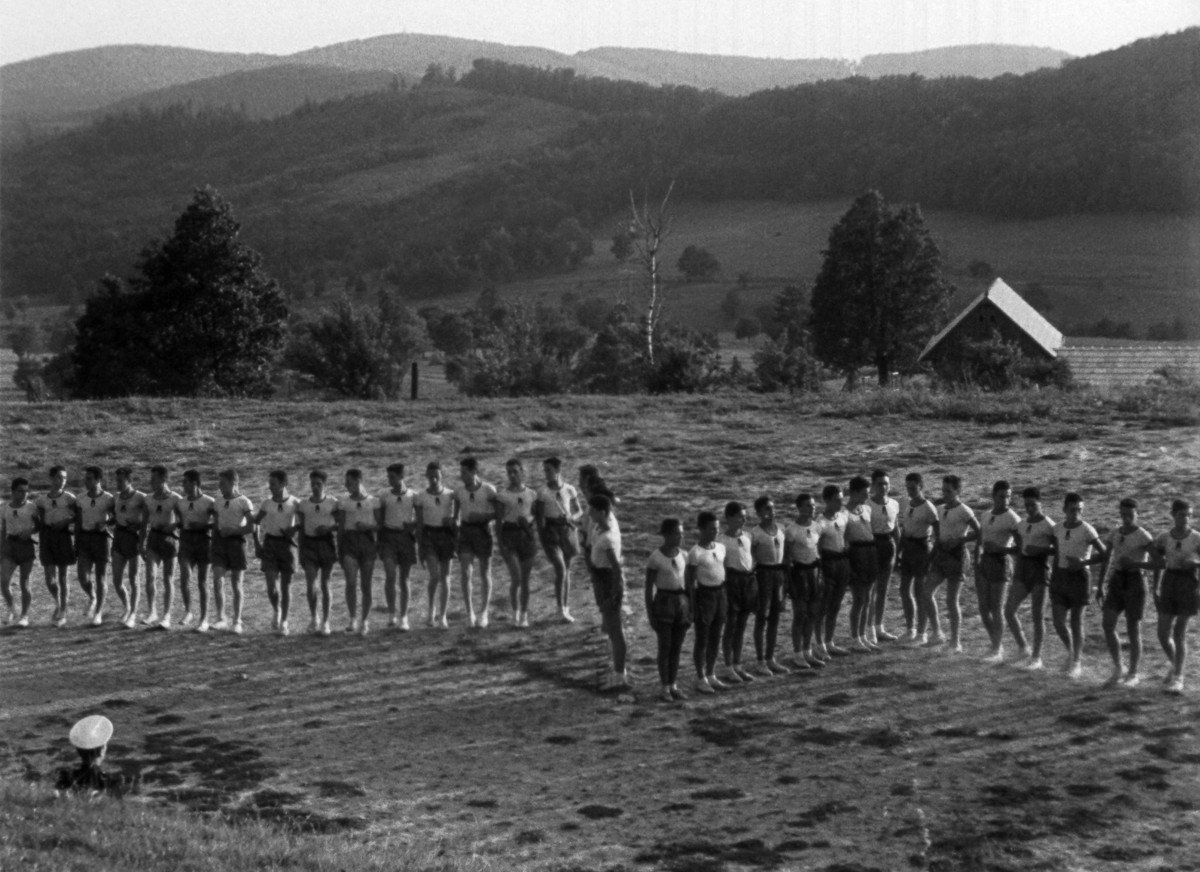

In the composition of the weekly, the majority of which was taken over from German propaganda, often quite aggressively, a large part of the domestic material also represented politics - the legitimization of the post-federal statehood, its representatives and institutions, the involvement of the state in the war, and its justification (reports from the Eastern Front)... Folklore was also promoted, as well as national identity - basically Blut und Boden, but also everyday life, cultural and social life, transport, industrial infrastructure and its construction, national economic achievements, Slovak beauty, and exhibitions about art and national economic progress... These were the quasi- “plus” values of film propaganda (= what we are fighting for).

Another side of it was chauvinism, the search for and conviction of the enemy, both internal (anti-Semitism, the anti-Czech agenda), and external (anti-Bolshevism). The Holocaust – the deportations that took place in Slovakia in two waves – from March to October 1942, and after the suppression of the SNP, while in the first case they were a matter of their own political initiative, which had no parallel in the satellite states of the Empire – we do not see any of that in Nástup. Either they were censored as being secondary, or these events were not recorded at all for the weekly, as a precaution.

But anti-Semitism (as one of the “tools” of Slovak fascism) is naturally present here. For example, in connection with the land reform (Interview of a journalist with peasants, Nástup no. 7 / 1938), in the taken-over jokes, or in the nationalist diction of some Slovak politicians. Another position of contemporary anti-Semitism was through imported German films in cinemas (e.g. Jew Süss and Ewige Jude), and the affirmative reactions to them, but also through the absent voice and lost talent of retired artists of Jewish origin.

Most of the shots of the Nástup weekly went “with the flow” of the regime, but we also find a few problematic ones, where today we consider their possible dissident subtext. For example, the report With your permission: “Little Piggy” (Nástup no. 253 / 1943) about pig farming, on a farm in Trebišov, is presented as an anthropological study of an Orwellian-style “pig party.”

In 1941, the so-called “production department” (leader and headhunter: Ladislav Faix, directors: Paľo Bielik, Eugen Mateíčka, Ján Fintora, cameramen: Karol Krška and Karel Kopřiva). Its authors, if they did not previously have that experience, became professional through practice, or short internships in studios in Vienna (Wienfilm) and Prague (Pragfilm). The first output of the production department was a series of five issues of the monthly LÚČ, each consisting of two or three shorter cultural views, in the range of 5-7 minutes. Subsequently, some separate, 10-15 minute documentaries were created, the topics of which essentially further developed the themes and “propaganda lines” of the weekly reports. Worthy of attention is the original film music, composed for the film by several musical modernists (Tibor Frešo, Šimon Jurovský).

Some more ambitious film titles remained in production at the end of the war (Kovačević’s film about the Demänovské caves In the Realm of Eternity, Martin Hollé’s medium-length colour film Hana Is Getting Married, whose filming was interrupted by the SNP), others were completed only after the war (Zimmer’s Black Art). Together, about a dozen more structured cultural films were created in Nástup, most of which have been preserved.

In addition to the ethnographic and beautiful Slovak titles (Under an Open Sky, Summer under the Kriváň Mountain), which are in a certain sense a continuation of the Plickov ethno-tradition, albeit conceived less romantically, a certain novelty exists in the genre, with national and economic themes, and their emphasis on the industrial modernization of the “neglected” Slovakia We Produce Glycerin, Artificial Fibres).

After the war, some of the entry films were screened under the banner of the Slovak Film Society, after the situational adjustment (with new introductions or commentaries). If the Nástup weekly newspapers were basically kept safe or served as material for secondary exploitation in archive-based compilation documents, unmasking the fascist regime, the national economic cultural images served a different purpose - as a certain school of “constructionist” propaganda, the experience of which was passed on quite seamlessly by the new regime.